Monday, Feb. 14 at 9 p.m.

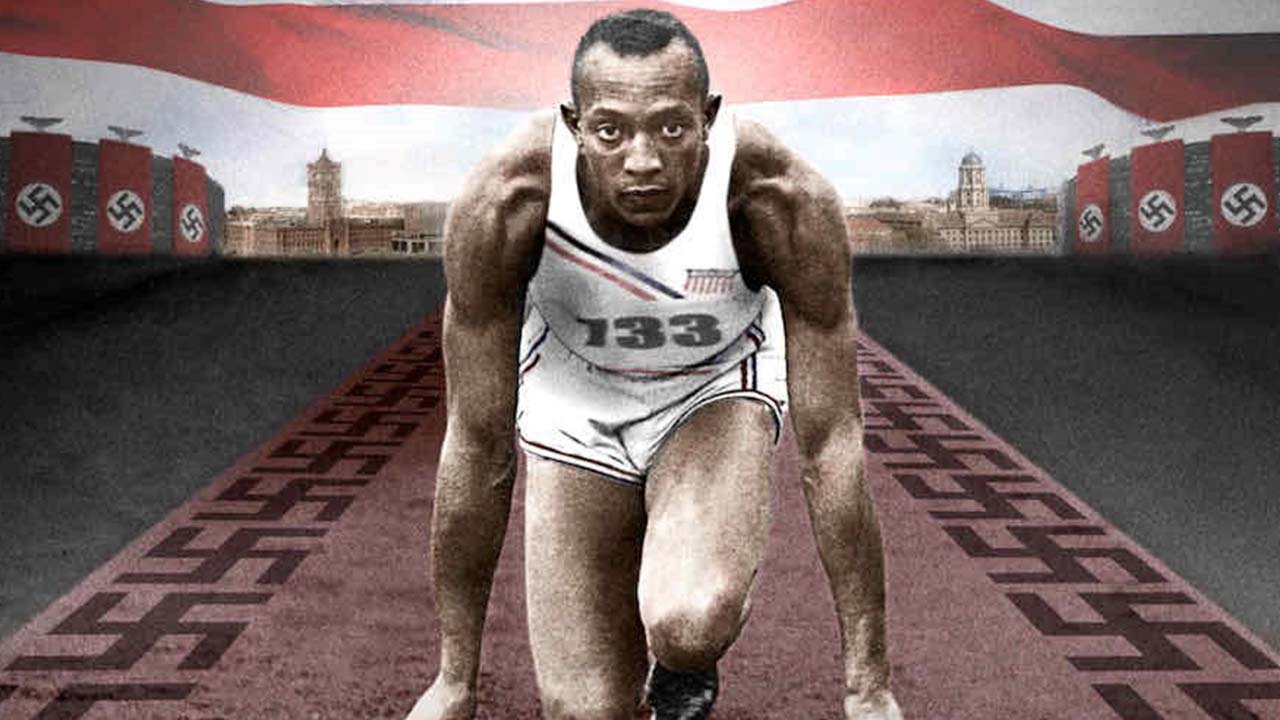

He was the most famous athlete of his time, whose stunning triumph at the 1936 Olympic Games captivated the world, even as it infuriated the Nazis. Despite the racial slurs he endured, his grace and athleticism rallied crowds around the globe. Yet when the four-time Olympic gold medalist returned home, he couldn’t even ride in the front of a bus. Jesse Owens is the story of the 22-year-old son of a sharecropper who triumphed over adversity to become a hero and world champion. But his story is also about the elusive, fleeting quality of fame and the way Americans idolize athletes when they suit our purpose and forget them once they don’t. Produced and directed by Laurens Grant and written and produced by Stanley Nelson, the team behind the Emmy Award-winning documentary Freedom Riders, the film can be viewed on PBS.org and the PBS Video App. Originally broadcast in 2012, Jesse Owens won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Research and received nominations for Outstanding Historical –Long Form and Outstanding Music & Sound.

It is hard to imagine a more politically charged atmosphere than the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Originally opposed to the idea of the games, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler was convinced by his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels that they were the perfect opportunity to showcase the superiority of Aryan athletes. Hitler presided over the opening day ceremonies, whipping the crowds into a frenzy of excitement. On August 3, when Jesse Owens stepped into the massive new Olympic Stadium in Berlin, the crowd went silent with anticipation, sitting on the edge of their seats to see the much-talked-about track star from America compete against the Germans. Running on a muddy track, Owens equaled both the Olympic and world records of 10.3 seconds in the 100-meter dash and won his first gold medal. Tradition called for the leader of the host country to congratulate the winner, but Hitler refused. “Do you really think,” the German leader said, “I will allow myself to be photographed shaking hands with a Negro?”

In his second event, the long jump, Owens dramatically beat the German favorite, Carl “Luz” Long, setting an Olympic record that stood for 24 years. The next day, against a headwind, Owens set a world record in the 200-meter dash, achieving his goal of winning three gold medals. Then, unexpectedly, Owens was ordered — against his wishes — to replace a Jewish sprinter on the 400-meter relay team. U.S. officials had changed the line-up at the last minute to placate their German counterparts by not fielding Jewish athletes. Owens won his fourth gold medal, the first African American to do so.

To understand the magnitude of Owens’ remarkable victories in the face of Nazi racism, the film begins in the poor Cleveland neighborhood where the young athlete grew up. A track star in high school, Owens was courted by a number of universities, but chose to attend Ohio State where, as a Black athlete, he was not allowed to live on campus. But adversity seemed to make Owens shine. Shortly before the 1935 Big Ten Championship, Owens injured his back and was told by his coach to withdraw from the competition. Owens refused — and went on to set three world records and equal a fourth.

Setting the stage for the 1936 Olympics, the film explores Hitler’s outsized ambitions for the games, and the movement within the U.S. to organize a boycott protesting Germany’s growing anti-Semitism. Owens, who had never put himself forward as a spokesman, was convinced by the NAACP to make a statement against the games, saying: “If there are minorities in Germany who are being discriminated against, the United States should withdraw from the 1936 Olympics.” But Avery Brundage, president of the American Olympic Committee, denounced supporters of the boycott as “un-American agitators.” Owens and other athletes were pressured to keep quiet and participate in the games.

The film also reveals the unlikely relationship between Owens and his German rival Luz Long, who, after his defeat, so respected his American competitor that he embraced him as the two marched a victory lap arm in arm. “Watching the footage of Jesse Owens and Luz Long is incredible,” said director Grant. “Long embraced Owens knowing the world would be watching — including a regime that would be displeased. But he was caught up with Owens ability and Long wanted to celebrate a true champion. I think the world’s best athletes often do that.”

Following the Olympics, Owens and his teammates were ordered to embark on a European fundraising tour for the Amateur Athletic Union. Tired, exhausted, and already separated from his wife for three months, Owens wanted to go home. Brundage threatened to strip Owens of his amateur athletic standing if he left, a threat which he made good when Owens departed. Now banned from competing in any sanctioned sporting event in the U.S., the athlete returned to a country with its own racial divide. On his first night back, he and his wife couldn’t find lodging in New York until one hotel finally agreed to rent them a room if they used the service entrance.

It is the rest of the Jesse Owens story that is the true triumph over adversity. Upbeat, positive, and determined, Owens gamely tried anything and everything — from running against horses for money to operating a dry cleaning business — to provide for his family. “Jesse Owens was able to carve out his own path and sustain himself, his family and his legacy during very troubling and limited times for Black men,” said Grant. “There were no endorsement deals for Black athletes. It’s incredible that he was able to achieve, survive and remain positive through it all.”

“He is the quintessential Olympic hero,” said Jeremy Schaap, ESPN reporter and author of Triumph: The Untold Story of Jesse Owens and Hitler’s Olympics. “He stood up to racists in Germany, he stood up to racists at home and he did it with a grace and a genius that have not been equaled.”