The lone survivor of the ill-fated Granite Mountain Hotshot crew has written a new book about the Yarnell Hill fire that claimed 19 members of the crew. Brendan McDonough’s book also talks about his life of drug abuse before the fire and how joining the crew helped saved him.

Video: Coming up next on "Arizona Horizon" -- we'll speak with the lone Granite Mountain hotshot survivor of the Yarnell Hill fire and we'll check out an exhibit of rare violins including a Stradivarius at the musical instrument museum. That's next on "Arizona Horizon." "Arizona Horizon" is made possible by contributions from the friends of Arizona PBS, members of your PBS station. Thank you.

Ted Simons: Good evening. Welcome to "Arizona Horizon." I'm Ted Simons. A vendor blamed by Secretary of State Michelle Reagan for failing to mail 200,000 publicity pamphlets for the May 15 special election says the Secretary of State is to blame instead adding the company's contract with the state expired months before Reagan's office learned of the problem. Arizona Capitol Times reports IMB claims its responsibility while under contract was to maintain and upgrade software and that the Secretary of State was responsible for using it. Attorney General Mark Brnovich concluded Reagan broke the law but there's nothing in statute regarding a remedy for penalty.

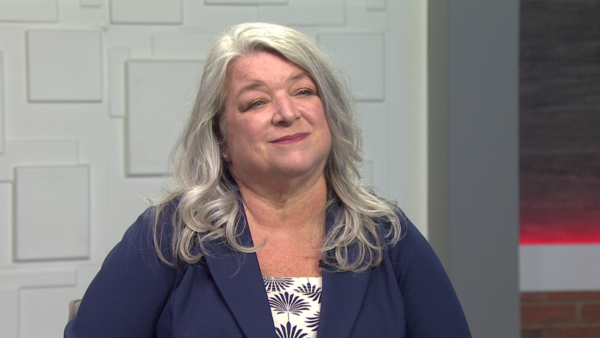

Ted Simons: Brendan McDonough, the lone Granite Mountain hotshot survivor, has written a new book about his relationship with his 19 team members who died in the tragedy. The memoir is titled My Lost Brothers: the Untold Story by the Yarnell Hill Fire's Lone Survivor. We welcome Brendan McDonough to "Arizona Horizon." Good to see you. Thanks for joining us.

Brendan McDonough: Thank you for having me today.

Ted Simons: I like to ask people how they are doing but with you I'm especially interested.

Brendan McDonough: I think I'm doing well for all circumstances and for everything I have been through I have had a lot of great support. A lot of breakthrough recently and just feel good. Feel healthy, feel in a really good place.

Ted Simons: breakthroughs by way of what? Counseling?

Brendan McDonough: with counseling -- a combination of a lot of things. Strengthening my faith, counseling, community service, just good work with great people.

Ted Simons: I ask it especially because we're heading into a rough time of year probably for you. When this time of year rolls around, last couple of times, difficult?

Brendan McDonough: Very difficult seeing the fires in the news. We have up in Canada fort Mcmurray fire, 1600 homes lost. Just continues to grow. We're starting to see the southwest with governor Ducey talking about it. It's tough but it's reassuring to me that we have great men and women out there that will continue to fight to protect people and homes and property.

Ted Simons: how did you become a hotshot?

back in 2011, I had walked into the office and asked if they were highing and literally five people had just quit within that first week. So I had an interview on the spot. So it was very fast paced. A little shocked and surprised but very happy that I had the chance to do that.

Ted Simons: But before that, though, you had a troubled action interesting, varied but troubled life. Talk to us about that.

Brendan McDonough: So six months prior to getting hired I was in jail for arrested for a crime. Right after jail I enrolled in an EMt class to try to do anything to better my life. It was really tough. It was a battle with drug addiction, feeling like a failure, as a father, as someone who wanted to serve the community but couldn't because of the mistakes I made. So that was kind of the battle I had before I got hired on.

Ted Simons: sounds like you wanted to change for your daughter.

Brendan McDonough: yes, very much so. I wanted to be a father for her, be the father I didn't have growing up.

Ted Simons: but you could have done many things. Gone in many directions to try to set yourself straight and prove yourself to your daughter. You chose being a hotshot. Why again that profession?

Brendan McDonough: it was something I always wanted to be a part of. Something that I knew I needed to do for other opportunities to open up within fighting fires.

Ted Simons: were you aware of the discipline involved?

Brendan McDonough: I think you can only understand so much before you go into a job like that. I tried to be as aware as possible, but when I got there it was a lot -- a lot of things that were new, a lot of things I didn't understand, a lot of things the guys taught me.

Ted Simons: when you first got there did you face skepticism? Here's a guy with a troubled past?

Brendan McDonough: oh, yeah. I came in later than any of the other rookies. I wasn't in even close to the shape that they were in, so a lot of that was very, very tough to beat. As soon as I did I knew when I was accepted I had great brothers that would stand behind me.

Ted Simons: Eric Marsh, the team leader, talk to is about his impact on you because it sounds like he took a chance on you, didn't he?

Brendan McDonough: He definitely took a chance on me. Second chance kid, I would say. One of the things Eric taught me besides being a firefighter is how to be a responsible person, responsible adult, how to be a father. Those are characteristics I learned from all of my brothers even though they weren't all fathers they had characteristics similar to what I needed to learn.

Ted Simons: when did you realize you could do this?

Brendan McDonough: I never doubted myself. I think that's how I was able to do it.

Ted Simons: Interesting.

Brendan McDonough: I guess I could never say never, but once I had gotten through my first few months of fighting wildfires I new this was my passion, this was the job I wanted and these were the men I wanted to be around. These are the type of people I wanted in my life that were continuing help me up.

Ted Simons: when did you know you had the confidence of your team members? Was there a point in time, okay --

Brendan McDonough: I think it was after my second fire when we were gone for 14 days and there was just back-breaking work, a lot of cutting line, a lot of burning, just a lot of -- doing what hotshots do. Just living up to that title. Once I believe they saw, hey, he's not going to quit, he's not going to give in, he's tough. He wants to work. He wants to be a part of this, he wants to be dedicated. I feel that's when I really gained their trust and understood what the brotherhood was.

Ted Simons: All right, what happened on June 30, 2013?

Brendan McDonough: for me, June 30th is a pretty difficult day to remember. A lot of trauma there. So getting to Yarnell, we were just assigned to a division and to get there to try to get an anchor in. That's what we tried to accomplish. It was just a very difficult day with the amount of resources we had and with the amount of fire that was there. It was a pretty small fire in sense of things such as fort Mcmurray that's almost 1 million acres. As the day went on, we just tried to delegate jobs. I chose to be the lookout. With different weather events, different communications and things like that we have the tragedy. We have 19 men dying.

Ted Simons: Back to the day -- as far as being the lookout, what could you see? Could you see the others from where you were? Your vantage point. You're the lookout. What were you looking out at?

Brendan McDonough: what I'm trying to look out for is I'm trying to see what's going on with the fire. I'm trying to have good eyes on it. I'm taking weather for them to see if there's any changes in the relative humidity, the wind, things like that. I could see them, I could make out figures. I couldn't see faces but I knew that was my crew, that someone was running a chainsaw. I could hear them.

Ted Simons: could you communicate with them?

Brendan McDonough: Yes, of course. There was a radio so I could communicate with them. Clear line of sight from them to me and from me to them.

Ted Simons: And they could communicate with you.

Brendan McDonough: correct.

Ted Simons: you could hear other communications they were sending and receiving as well?

Brendan McDonough: Some of them.

Ted Simons: not all.

Brendan McDonough: correct. You can't expect someone to be able to pick up every single communication on ten different channels.

Ted Simons: right.

Brendan McDonough: your main priority is to your crew and to really go above and beyond that as your superintendent, captain, squad bosses. One channel I was listening to was the weather channel. That was something I was trying to scan.

Ted Simons: when did you know things had gone horribly wrong?

Brendan McDonough: I knew -- that's a tricky question. I knew things were going horribly wrong when I started seeing homes get burned. That's horribly wrong. That's not something you like to see. When did I know my brothers were in horrible danger? When I heard it over the radio. That's when I truly understood how close they were, the position they were in, asking for water drops, things of that sort, trying to get those communications with the proper people. That is when I started to feel the anxiety about this could end well, even bad.

Ted Simons: ask this question so many different ways to so many different people. Why did they leave a relatively safe, burned, black area, and go back into that canyon?

Brendan McDonough: Based on decisions and based on communications, based on information they had and were given. You know, as hotshot superintendents they make decisions based on information they are given, information they are seeing, what they are seeing, hearing and getting. That was the decision why they left the black what those communications were I wish I could answer. I really can't as of this moment.

Ted Simons: yeah. I ask you that because there have been critics who say maybe you know a little bit more but your loyalty especially to Eric Marsh keeps maybe you from saying everything you know.

Brendan McDonough: no.

Ted Simons: You don't agree with that?

Brendan McDonough: No, I do not agree with that. I have been completely up front and honest. I think what we're coming to find is there's a few people investigating Yarnell Hill fire tragedy and they are finding a lot of up in findings on what happened that day and it's not because it was lack of discipline from the investigation, it wasn't a lack of training, just a lack of time. Lack of time and resources for them to be able to truly get into this investigation. So I think there's a lot of things that we're going to come to learn and we'll continue to grow as a community in the wildfire community we're going to continue to grow whole, to learn from the decisions made not only from Eric Marsh but a lot of other people including myself.

Ted Simons: One last thing about this, some suggest maybe you did hear that order. You know who ordered them or you had a better idea of why they left the black. Again, these are people trying to find out what happened.

Brendan McDonough: yeah.

Ted Simons: Is that a valid observation?

Brendan McDonough: No. I do not know who ordered them to leave the black. I do not know who asked them that, but I know there are people looking into that. They found radio transmissions that they are trying to match voices to and trying to figure out what's being said and who is it being said to. It's a long process. You look at a lot of wildfire tragedies. It takes us years to grow from. It's not that we're stubborn or ignorant. There's a lot of information there, a lot of possibilities when you're fighting a natural disaster. Look at tornadoes, tsunamis. Do you send in crews there in the heat of the moment? Do you sends in people to go fight these natural disasters? We're fighting a very diverse problem, so when something like this happens, it's very easy for people to point the finger and I'm just glad that we have such great men and women in this community willing to take the time to dedicate to truly finding out what happened so we can prevent this.

Ted Simons: you understand why people ask the questions.

Brendan McDonough: of course.

Ted Simons: it still seems vague. When something as tragic as this happens people want to know. And they want to know what to fix. Have we learned lessons from this?

Brendan McDonough: I think we have a few lessons that we have learned. I have seen the tactics people are using to fight fires, being a little more cautious with deciding making, thinking twice about doing something. They are looking at new shelter designs. By learning those lessons that's what continuing to investigate into this fire is about. It will just continue to grow.

Ted Simons: but didn't you write that nothing has really changed?

Brendan McDonough: Nothing has changed resources-wise, as a whole we need to stand behind these men and women. They are spread so thin. There's no denying wildland fires are getting more thin. We need more resources. They are trying to keep up with the pace of the wildfire seasons that we're seeing. They are becoming year round now. They are becoming more often. They are becoming larger, more destructive. With that we're trying to keep up.

Ted Simons: Your reaction. The hours, the days, the weeks afterwards. It sounds like -- I think everyone can understand rough time for you.

Brendan McDonough: Yes.

Ted Simons: talk to us about it.

Brendan McDonough: It was a very rough time. It's not that often that you bury 19 men in a very short amount of time. It's not often that you go to 14 funerals and you try to be strong and try to represent them in a whole. At that age I didn't understand what those feelings were. I didn't know about trauma. I didn't know about grief. I didn't know about PTSD. So it was all very new for me. Leading up to the time that I realized what I was going through, it just continued to compound and get worse. I mean, it was a good year before I had even received counseling, before I started going to counseling. During that year it was all trauma, anxiety, depression, what's wrong with me? Those feelings of self-doubt and guilt.

Ted Simons: sounds like you came very close to committing suicide.

Brendan McDonough: yes.

Ted Simons: what got you through past that incident into therapy? What was the breakthrough?

Brendan McDonough: I think just knowing my purpose, knowing my purpose here is to be a father. That was what I needed to remind myself of, to be a good Steward of my family. To be a good person in my community. People look to me for answers like you're asking, and sometimes I hope I can be there to answer them. The ones I can't answer I'm willing to admit I don't know. Just finding that purpose again. That's what really got me through that. Having such great support from my community, my counselor, having my faith has been tremendous.

Ted Simons: What's next for you?

Brendan McDonough: What's next is just continue to be a good dad, continue to try to be a person of service to my community. Trying to help, you know, fire, police, EMS, veterans with one of the nonprofits I work with carries the load. They have done amazing things. Truly blessed to be a part of that and see what they do. Just to try to help. I mean, from a young age that's all I wanted to do. I wanted to help. I would like to go back to school, take the time to go back to school, learn, get an education so I can continue to give back in some sort of manner.

Ted Simons: congratulations on this book. Sounds like it's doing well. It's a very interesting read. Congratulations for fighting through all that as well. You got a long life ahead of you.

Brendan McDonough: thank you.

Ted Simons: good luck and thanks so much for joining us.

thank you for having me. I really appreciate it.

Video: the Colorado River has carved over 600 miles of canyons in southern Utah and northern Arizona. As sublime as the chasms are to travelers they pose a seemingly insurmountable problem. Just how do you get to the other side? A highway marker on U.S. 89-A commemorates a successful effort that for nearly 06 years did just that. Lee's ferry. Mormon pioneer John Lee came here in 1871. He established a ferry service across the Colorado River at the only natural point for 600 miles. Lee, seen here seated on his coffin, was executed in 1877 for his role in the mountain Meadows massacre when 120 emigrants heading to California were murdered in Utah. The ferry operated for 52 more years, transporting thousands of hikers, horses, wagons even small automobiles across the river. Only the railroad and finally in 1929 the and a half hop bridge made Lee's ferry obsolete. Today, the original Navajo bridge is reserved for pedestrians while the new Navajo bridge built beside it in 1995 caters to cars and trucks. While the ferry itself is long gone, the name remains. Lee's ferry is now the terminus for thousands of awe-struck sightseers rafting on the mighty Colorado River.

From the internationally famous Riverside park ballroom in Phoenix, Arizona, we present one of the nation's great western swing dance bands, all the western playboys. [Singing] ¶ well I ain't got nobody ¶¶ ¶ and nobody cares for me ¶¶ ¶ oh, the shark has sharp teeth dear ¶¶ ¶ and it shows them pearly white ¶¶

Ted Simons: Tonight's edition of Arizona Art Beat focuses on the Stradivarius violin, a name synonymous with excellence for 300 years. Experts say the sound is unlike any other and is as close to perfection as possible. Shana Fischer and photographer Langston Fields take us to the musical instrument museum. [playing the violin]

Video: The sound is literally music to your ears. in the hands of the celebrated virtuoso Yitzhak Pearlman it's a revelation. The Stradivarius has been called the finest instrument ever made. Antonio Stradivari lived in the 1600. During his lifetime, an astonishing 93 years, he created 1100 instruments, a little more than half were violins.

Richard Walter: He is recognized for a whole variety of skills he brought to the violin. He didn't invent the violin but he did create them at a very, very high level. That ranges from application to the varnish to the surface to the proportions and design of the violin we recognize as the quintessential violin now. Details of carving. He was excellent with a hand tool and was always exploring different ways to make it sound better.

Video: Experts say in addition to his incomparable skill the exquisite sound comes from simple beginnings.

Richard Walter: we celebrate here the fact that Cremona, Italy, was close to a forest, a location of wood that grew with very particular climate ands conditions and altitudes and all these things that made it perfect for making acoustic musical instruments.

Video: The exhibit showcases work from other great violin makers including Guarneri. Del Gesu was a contemporary of Stradiveri and the most expensive violin ever auctioned off was one he created, it went for $18 million. That's what makes it so extraordinary. You have the chance to view instruments carved hundreds of years ago by the masters and connect with that history.

Richard Walter: The target gallery here at mim like all our galleries is filled with audio visual monitors. People come in with their head sets and not only see the instruments in beautiful 360 degree view so you get this great, intimate look at the instruments themselves, we also have portrayals of luthiers, instrument makers. We have fine professional performers so they can help people understand from so many perspectives what makes a great violin so great. Is it the way it's built? The way it sounds? Is it the way it looks?

Video: Walter says to fully enjoy the exhibition pay attention to details. He says every luthier, that's someone who makes a stringed instrument Harks a unique signature, almost like a fingerprint.

Richard Walter: you look at the scroll, which is one of those signature areas where people say Stradivari crafted a scroll in this fashion and others had sharper edges, softer edges, all these things. In those regards you can really see those identifying features.

Video: you can witness the physical changes in violins throughout the years. When you look at this AMADI from the side you can see the middle curves out, almost swollen. This produced a very intimate sound, one that didn't carry far and didn't need to. It was only played for a small group. Look at the Stradivarius, crafted about 100 years later. The middle has just a slight swell to it. Just that small change in the curve allowed the violin to project the sound that could reach a large crowd.

Richard Walter: that's really one of the signatures of his violin legacy is that the sound is preferred by fine concert violinists knowing they will have a very expressive instrument that can project into a large audience.

Video: one of the more interesting displays are the tools used to make the instruments. This is the first time they have been on display in the United States. There's also an opportunity to learn about violin making today as well as hear violinsist Rachel Barton pine play her beloved del Gesu. In all the exhibition is an opportunity to step back in time and appreciate craftsmanship that continues today.

Richard Walter: we hear people all the time comparing the different woods. This one is beautiful. This is darker. This looks bigger. So we're giving people that opportunity not just to see beautiful violins but to learn something about how to appreciate them as individual works of art, individual musical tools, and the products of a lot of people who are still aspiring to build things at the level Stradivari did in his time.

Ted Simons: The Stradivarius exist Biggs is at the museum until June 5th. That weekend the mim will also put on their celebrate Italy event where you can sample traditional food. For more information visit mim.org.

Ted Simons: Wednesday on "Arizona Horizon" Phoenix mayor Greg Stanton will join us. We'll hear from a local journalist about her new book onto raising a child with down syndrome. That's on the next "Arizona Horizon." That is it for now. I'm Ted Simons. Thank you so much for joining us. You have a great evening.

Video: "Arizona Horizon" is made possible by contributions from the friends of Arizona PBS, members of your PBS station. Thank you.

Video: Funding for the Arizona arts and culture fund is made possible by signal society members, Eleanor light and Judith Hart and by -- you can become a curator of the arts on Arizona PBS. For more information call --

Brendan McDonough: Author: "My Lost Brothers"