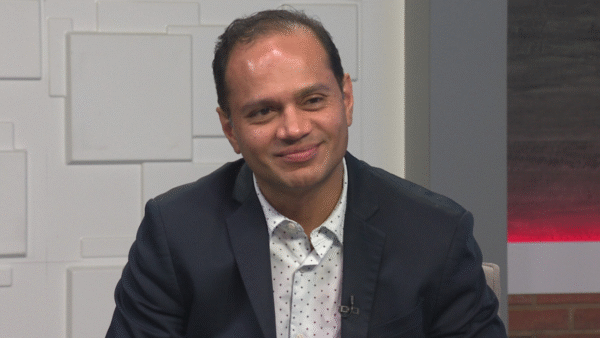

A state lawmaker would like to see the end of automatic citizenship for virtually everyone born in the United States, as granted by the 14th amendment. Arizona State University Law Professor Andy Hessick talks about the 14th amendment and the possibility of changing it.

Ted Simons:

The 14th amendment of the u.s. constitution gives citizenship to almost anyone born in the United States, regardless of the legal status of the parents. But there is a move to eliminate this automatic citizenship, led by state senator Russell Pearce, who recently announced plans to introduce legislation to address the issue. Here to talk about the 14th amendment is Andy Hessick, a law professor at Arizona State University.

Ted Simons:

Thanks for joining us. What does the 14th amendment say?

Andy Hessick:

It says that all persons born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the state in which they reside.

Ted Simons:

Ok, seems clear. When was it added to the constitution?

Andy Hessick:

1868, I think.

Ted Simons:

The reason it was ratified?

Andy Hessick:

It was added to the constitution because in the Dred Scott decision, in the 1850s, the Supreme Court held that African American couldn't be citizens, they were a category of people excluded and so the amendment was necessary in order to ensure those people, the African Americans, could be citizens.

Ted Simons:

So it was targeted pretty much toward African Americans?

Any Hessick:

That's right.

Ted Simons:

At the time, as far as you can tell, was there any discussion regarding illegal immigrants?

Andy Hessick:

There wasn't any discussion about illegal immigrants, but there was discussion about different groups of people who would become citizens. For example, there was a debate whether this amendment was appropriate because it would result in the children of Chinese people or gypsies, I think they said, becoming citizens and there was hesitation about that. And -- and they talked about it and the senators agreed that this amendment would, in fact, extend citizenship to those children.

Ted Simons:

Even at that time, they knew there were a couple of question marks but thought they could be included.

Andy Hessick:

That's correct of though they didn't phrase it in terms of illegal immigrants.

Ted Simons:

30 years later, a case involving Chinese immigrants.

Andy Hessick:

In that case, it involved whether a person who was the child of two Chinese subjects, Chinese citizens who had been in the United States, he was born in the United States, although his parents were Chinese citizen, the question was whether he was a citizen of the United States. But that's the important question.

Ted Simons:

What was the discussion like? What were the concerns?

Andy Hessick:

The supreme court said -- well, the concern they didn't want just anyone in the United States to be a citizen and the Supreme Court said well, anyone born essentially in the United States is a citizen, with two exceptions. And the first exception is the child of a diplomat. And the second exception is when the child is born to foreigners who are occupying -- occupying the United States. If they were hostile invaders and if they'd been born in that context. And I think there's a case from 1819 or so, or maybe a little bit earlier, in which the child of a British subject -- or, born in the United States territory was deemed not to be a citizen because they were born at a time when Britain was occupying part of the United States.

Ted Simons:

Right. So we've got the 1898 case that took on the 14th amendment and seem to have a clear ruling and yet there are those who are saying that needs more clarification. We still aren't quite sure if this is what the 14th amendment really says. Talk to us about that.

And Hessick:

Right, some people say maybe the 14th amendment wasn't meant to or shouldn't extend to the children of illegal immigrants. In terms of clarification, maybe they mean sort of correction, just a different interpretation. At this point, for them to sort of succeed in getting that different interpretation they would have to go to the United States Supreme Court and get the you had Supreme Court to agree with whatever interpretation they want to have.

Ted Simons:

Have there been attempts between 1898 and literally now to get that clarification, correction, however you want to put it?

Andy Hessick:

Nothing serious I'm aware of. I haven't checked everything. But -- but the 1898 case seems to be regarded as solid law that hasn't been seriously challenged.

Ted Simons:

You were talking about the subject to the jurisdiction thereof and senator pierce says those not here without proper documentation are not subject to U.S. jurisdiction. Is that a valid point?

Andy Hessick:

I don't think that's a valid point. I think it's a dangerous point to make.

Ted Simons:

How come?

Andy Hessick:

Because jurisdiction means power and if we say that someone is not subject to the U.S. jurisdiction, that means the U.S. has no power over that person. That means they could commit murder or federal offenses and the United States has no power over them.I don't think we want to take that position. If anything, we want to be able to exercise power over them.

Ted Simons:

When he says you can't draft these folks into military service or they can't serve on a jury and those things, we don't have the power to enforce those types of activity, you're saying -- what? -- that's a camel's nose under the tent kind of thing?

Andy Hessick:

We have jurisdiction in other respects, the criminal laws and within the bounds of the United States, they're subject to the laws the United States.

Ted Simons:

Another law maker says the subject to the jurisdiction thereof applies to those whose sole allegiance is to the United States, valid?

Andy Hessick:

That is -- I understand where he's coming from, because it depends on ancient English common law but it's way too technical relying on an old doctrine of allegiance to the king.

Ted Simons:

One other point, additional laws had to be made for American Indians born on reservations to become American citizens and if they have to take that step, why not a step regarding those of parents here with undocumented -- without the proper authorization?

Andy Hessick:

Right, American Indians are a special situation. There was a carve-out for the Indian, the native Americans and although that language was dropped, the Supreme Court has interpreted this provision, early on, they interpreted it not to CONFER citizenship, because it indicated the intent of the drafters, not to include.

Ted Simons:

Because that was originally a special case, it had to be addressed as special?

Andy Hessick:

That is right.

Ted Simons:

The concept of a state perhaps issuing a different kind of birth certificate as opposed to -- whatever federal guidelines there may be. Can I state do that?

Andy Hessick:

Well, so right now -- I want able to find any specific federal guidelines requiring the issuance of a birth certificate. There are certain requirements of birth certificates if it's going to be issued it has to meet requirements but actually just a state law requirement. I don't think right now, there's a problem necessarily with the state refusing to issue a birth certificate or issuing a different type as long as it meets minimum requirements. What problems might arise, in failing to issue a birth certificate to certain types of people, it might be viewed as discrimination or might infringe other types of rights. If a birth certificate is required for voting, then you can run into problems.

Ted Simons:

If you deny access because of this particular birth certificate, that could be trouble.

Andy Hessick:

That's right.

Ted Simons:

As it applies now and considered, they say they want to get this passed through the legislature and 13 or 14 other states and get the Supreme Court to look at it and think the Supreme Court will look at it and say that's not what the original intent was to allow illegal immigrants to have citizenship.

Andy Hessick:

Right, so I think that -- it's possible, it's very hard to guess what the Supreme Court is going to do. I think the difficulty is going to be that many people on the Supreme Court right now like to look back at history. That's their principle method of interpreting the constitution and the decision in 1898 catalogs up history. And that history consistently says that anyone born in the United States, so long it doesn't fall within dip mats or hostile enemies --

Ted Simons:

Good to see you thanks for joining us.

Andy Hessick:

Thank you.

Andy Hessick:ASU Law Professor;