A tribute to our military veterans featuring the work of the Veterans Medical Leadership Council; the heroic story of Sylvestre Herrera, the first Arizona resident to receive the Medal of Honor during World War II; and Betty Blake, one of the original Women Air Force Service Pilots who were trained to fly military aircraft to support the war effort.

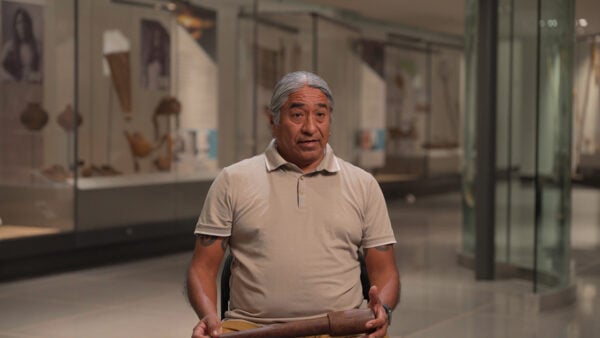

Ted Simons: Good evening. Welcome to this special Veterans' Day edition of "Arizona Horizon." I'm Ted Simons. On this day America honors the men and women who have protected our nation's freedoms by serving in the U.S. armed forces. Making sure those veterans are taking care of is the year rounds mission of the Veteran's Medical Leadership Council that helps with a variety of financial and health care needs. I spoke with its president, retired U.S. Air Force colonel Sam Young. Good to have you here.

Sam Young: Thanks. Good to be here.

Ted Simons: Let's start with the basics. Veterans medical leadership council. What is it?

Sam Young: It's an interesting name, but essentially it's a volunteer organization consisting of volunteers who are veterans who served during time of combat have come together to give back to those veterans that need some assistance. It started in 1999, was put together essentially through the V.A. medical center volunteers to help articulate and encourage initiatives to help veterans and then ultimately to help sponsor the parade and then follow on to help the troops that have fallen on hard times.

Ted Simons: Was at the kind of thing where not necessarily outside voices, these are veterans for the most part, was it a thing to maybe get a different viewpoint on things at the V.A.?

Sam Young: People that had been there, done that, it's very hard to articulate what the military is about in a civilian community some of the there was some identification with that and of course large veterans medical center which handles about 87,000 patients. So veterans can talk a different language.

Ted Simons: Indeed and they can also help with fund-raising. How much what goes on there, how much of that falls outside state and federal funding?

Sam Young: A large part that has to do with individual needs of the people. Say, for example, paying of utilities. People, somebody's car that breaks down. Or sometimes you need to put food on the table. Or you need clothing or whatever that happens to be. That's one category for the actual veterans themselves. Then you also have other initiatives, for example in the state home we were able to put together a project to remodel the outside patio so it was safe. We came together to help do that. There are little initiatives like that, but things outside the federal and state government.

Ted Simons: Things that fall through the cracks that occur in the day-to-day living.

Sam Young: That's correct.

Ted Simons: Some of the programs, you refer to it as the returning warrior program, that deals with things like jobs, getting your car fixed, these things.

Sam Young: Returning warrior program, with 911 and certainly with Iraq and Afghanistan, we started to finds some of the veterans that were coming back that were in need of support. As that number grew from 3,000 to 6,000 to 9,000 to 15,000 we put together the program. We deal directly with the social workers at the V.A. hospital. Now, it's all anonymous. We don't want to know who needs help and who doesn't. What the social worker does is work with that particular veteran, see what the needs are, see what the funding is for them and we provide a little bit of a financial safety net. The fact that there's only 18 of us we're able to cut a check in hours to help somebody that may be evicted or somebody that they are shutting off their utilities or their car is broken they can't get to work or can't make a medical appointment or something like that.

Ted Simons: How common are those things?

Sam Young: Very common. Just in the first six months we were able to raise and spend over $200,000 just this year. So we consider veterans, whether it's Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, you know, we reach out to all of them but we rely primarily on the social workers at the V.A. medical center.

Ted Simons: For some, of course, they need more assistance than others. Support to homeless veterans. You're involved with that as well. Everything from dental care to maybe just providing a way to have a reunion with their families.

Sam Young: That's exactly right. We work with U.S. air. We had a veteran from World War II that was in Iwo Jima and that he wanted to participate in a flight to the World War II memorial in Washington D.C. but he couldn't go because he needed a care-giver some of the we were able to fund the care-giver to escort him to satisfy a lifelong dream for him.

Ted Simons: That's fantastic. As far as community advocacy, we first med at the dedication for the Herrera way.

Sam Young: Yes.

Ted Simons: That was there on 3rd street?

Sam Young: Yes.

Ted Simons: Those things you're involved with as well.

Sam Young: We touch whoever needs help. For example, the stand-down. There's an annual stand-down run by a specific organization. We help support financially and we volunteer to go down. This last year they helped almost 1300 veterans that were essentially living on the street homeless or those that needed assistance, whether it's a hair cut, a good meal, registration through the V.A., whatever happens to be.

Ted Simons: The state veteran home, that needs improvements too. That needs help and you provide support.

Sam Young: We go to them and say how can we help. Essentially. We were able to help in one case when they needed kind of like those special insulated covers for the meals. So we try to give back wherever we can. In some cases we can make a difference.

Ted Simons: I notice as well that women veterans were a focus. Sometimes people forget that there are needs there as well.

Sam Young: There's roughly 46,000 female veterans in the state. A lot of times the homeless female veterans kind of go unnoticed. We were involved with a place called Emily's place. Essentially that was to kind of like take an existing facility and paint some walls and work with the city and also veterans first to put together that for some of the homeless women.

Ted Simons: Biggest challenge now, females face. What do you see?

Sam Young: The challenges that the conflicts are not on the front page any more. The veterans are. It's a 365 day a year requirement.

Announce: We want to hear from you. Submit your questions, comments and concerns via email at arizonahorizon@asu.edu.

Ted Simons: A Phoenix street, a school and other local landmarks are famed in his honor. Sylvestre Herrera was the first Arizona resident to receive the medal of honor during World War II. He passed a way in 2007 but left a legacy that lives on. Mike Sauceda reports.

Video: Oh, beautiful for spacious skies for Amber waves of grain for purple mountains majesty above the fruited plain.

Mike Sauceda: It was not even his war but 84-year-old Sylvestre Herrera didn't find that out until he was 27. That's when his father told him he was really his uncle and that Herrera was not a United States citizen. He had been brought to El Paso as a baby when his parents died and moved to Thomason when he was 12. His uncle told him he didn't have to go to war after being drafted, but he had a family and that was their country.

Sylvestre Herrera: That us was the hardest part for me. Leaving my family.

Mike Sauceda: This was the country he loved, so in January of 1944 Herrera was drafted into the Army, spent time in boot camp and on furlough and seven months on the front line fighting Nazis in Europe and Africa the 36th infantry division. On March 15, 1945 his odyssey as war hero was sealed. He was fighting near the French-German border.

Sylvestre Herrera: We ordered to advance. I was first scout. I was in front. About quarter mile ahead of everybody. My second scout and I we were always in the front. We were advancing, we were stopped by artillery. We took cover.

Mike Sauceda: With his M-1 rifle similar to this and a hand grenade he took out a NAZI machine gun nest. Then he went where only Angels and war heroes dare tread, into a land mine field surrounding a second machine gun nest. His foot found one land mine, another blew up. Both feet were gone.

Sylvestre Herrera: I kept firing at them. I think I shot about three guys from that -- from that machine gun. Because I have to because they would get me. I was right in the center. One hit him in the shoulder. So after that I almost passed out. That's when my squad finish up.

Mike Sauceda: But Herrera never passed out. What kept him going?

Sylvestre Herrera: Love. Love of country, love of my fellow man.

Mike Suaceda: He was saved by this medic and when medical personnel treated him they pride this rock from his clenched fist. He later made it into a necklace. He had other exploits before he was injured like this tank he took out with a rifle grenade launcher. He says it spun round and round because only one track was intact. On August 23, 1945, while on furlough in Phoenix, he received this tram informing him he was going to be awarded the country's greatest military declaration, the Congressional Medal of Honor. He traveled to Washington where President Truman placed it around his neck, a day where 28 veterans were honored.

Sylvestre Herrera: Back then -- but yeah, I'm proud of it, but I don't go out telling, hey, I got the Medal of Honor.

Mike Suaceda: He says Truman is his favorite president.

Sylvestre Herrera: He didn't take no Brook from nobody. Reminded me of myself.

Mike Suaceda: His no bull attitude got him in trouble a few times but it's an attitude that makes war heroes.

Sylvestre Herrera: I was a private first class. I made sergeant three times and I was busted three times. For fighting an officer. He gave us an order, and I lost most of my squad, so I went over there and got in it with him.

Mike Suaceda: Herrera says his Mexican heritage may also have helped him in battle. His great uncle fought alongside Pancho Villa. He was given a parade in Arizona.

Sylvestre Herrera: I was all scared! I didn't know what to do.

Mike Suaceda: Arizona residents raised $14,000 so Herrera could buy a home. He bought two and a half acres and have this home which now stands vacant built on the land. He's a hero in the classical sense but has mixed feelings.

Sylvestre Herrera: It's not too fond to remember things, to have to kill people to be with you are, but we had no choice. We had to fight back.

Mike Suaceda: Herrera is the only man in history to have both the congressional medal of honor and the Mexican equivalent. He received his citizenship during the war. He says awards won by him and other Hispanics helped Latinos.

Sylvestre Herrera: Yeah, it did. Uh-huh. Yeah. We got up a little notch higher.

Mike Suaceda: After the war, Herrera went to school on the G.I. bill and became a leather tooler. He also learned silversmithing and made his living with both trades. His command room is where he keeps his medals and other memorabilia. Pictures of him and other famous people abound. It reflects his heroic nature. He has five kids, 11 grandkids, three great grandchildren. His wife Ramona died in 1978. Although the world paints him as a hero he doesn't feel he is one.

Sylvestre Herrera: No. It don't bother me one way or the other. I don't like to act big because that belittles me.

Ted Simons: Women Air Force service pilots known as the WASPS were the first women trained by the Army Air Force to fly military aircraft N. a moment we'll meet an Arizona woman who was in one of the first classes of loss known as the Guinea pigs. First here's part of a story we aired on Horizon in 1996.

Video: From 1942 to 1944, over 1,000 women earned their wings to become women Air Force service pilots and fly military aircraft during World War II.

Video: We flew all of them. All of them. We flew all the big bombers, the B-26, B-25, the B-38. We have that, that's our gift you see. Can't take that away. Oh, yeah, winter flying. I'll tell you, that was something else. Did you ever get as cold in your life as you did?

Video: Your feet always froze.

Video: For these two, photographs in a scrapbook bring back memories of their days in the WASPS.

Video: I went in originally into the fairy command at Dallas. That's when I buried some of the AT-6s. You pick them up at the factory and take them when they were needed at different air bases.

Video: All of the girls that I know, in fact I would be safe saying all of the WASPS were very dedicated. Wanted to fly more than life itself. Had the bug bad.

Video: Women Air Force service pilots flew every kind of noncombat mission imaginable. In doing so they were able to free up male pilots to fly in combat overseas where they were critically needed.

Video: Women had never had this opportunity before. And you realized that you were -- if you failed, you had lost a big opportunity for women.

Video: Two women are credited with creating the wasp opportunity. Nancy Harkness Love had pioneered a program where top women pilots transported military aircraft from factory to field. Jacqueline Cochran started an experimental women pilot training program with the goal of utilizing women pilots to fly a variety of missions. These two programs eventually merged forming the women Air Force service pilots or wasp.

Ted Simons: Some of the women interviewed for that story have since passed away. They weren't around when members of the WASP were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. For a long time they were some of the unsung heroes of World War II. They were civilian employees who didn't receive veteran's benefits until the late 1970. I spoke to Betty Blake about her Mel tear life and her experience as a WASP. Thank you so much for joining us on "Horizon."

Betty Blake: I'm very happy to be here. I'm flattered.

Ted Simons: No, we're flattered. You have so many stories. I want to start from the very beginning. When did you know you wanted to be a pilot?

Betty Blake: Well, I was the only girl on the boys' baseball team. And I was the catcher. And the pitcher got his private license, so he invited me to be the first passenger. Well, I just because somebody had a license I thought he knew everything about flying. He really didn't but I was lucky that day. But I had never been to the airport. I had read all the books by Amelia Earhart and Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, Lindbergh and everything, but I had never even been to the airport but I was interested in flying even then.

Ted Simons: You wound up soloing at the age of --

Betty Blake: 14.

Ted Simons: 14. How did that come about?

Betty Blake: I got a job sending out the bills to the students at the flying school where I had had the ride. And he would sort of farewell toward me. He gave me free flying time. There were several Navy pilots that instructed on their time off because this airport was in Honolulu, very close to Pearl Harbor. So they were Navy pilots flying -- they would come on their time off and instruct. So I had a Navy pilot instruct me and he gave me a lot of extra instructions whenever he didn't have a student he would take me up. I had a lot of extra time, very luckily.

Ted Simons: When you were in the air even at that young age you loved it?

Betty Blake: I loved it. I wore my grandmother's lucky ring and there were times when I was Northrup and it was very bumpy and rough air where I rubbed the ring a few times and said a silent prayer. After a few times I was hooked.

Ted Simons: I'll bet. You mentioned Amelia Earhart. You were born in Hawaii, raised there before it was ever a state. I want to hear your Pearl Harbor story. You met Amelia Earhart.

Betty Blake: Yes. She came to the Island to fly the Pacific, be -- no, to fly from Honolulu to Oakland, California. She was the first woman to do it, and to fly solo. The night before she was to take off she gave a talk at the University of Hawaii. Well, my father, I was 14, my father drove me up there. I was very interested in flying. I sat in the front row. I was the only kid in the audience, so after the talk she came directly to me, all the adults were standing around waiting to shake hands with her. I think they were ready to wring my neck. She was interested in knowing why I was there. She invited me out to watch her take off the next morning for Oakland. My father drove me out there, and she took me into her twin-engine plane and we sat, she showed me the instruments and we talked for a few minutes and laughed a little because I had a separation between my two front teeth at that time, so did she. So we became buddies because of that. Because of our separations.

Ted Simons: You got a chance to watch her take off.

Betty Blake: Yes, I watched her take off. I didn't watch her take off. She started to take off, and before she got off the ground she pulled the throttle back and taxied back and my father was tired of waiting and he says, come on, we're leaving. She took off later that day and made it to Oakland but I wasn't there to see her take off.

Ted Simons: As far as joining the military and become ago pilot for the military.

Betty Blake: I was a pilot before Pearl Harbor. Hi an instructor's rating and commercial license. I was flying tourists between the Islands in little cub put-put planes between the Islands. But when you're 21 you're immortal. You don't worry about things. But it all stopped of course at Pearl Harbor. Then my husband was transferred back to Philadelphia to a new cruiser, and so I went with him. We got married and I went back with him. Just about that time Nancy love went down to Wilmington, Delaware, and found records of woman pilots I guess the records in Washington D.C. about licenses and they called me and asked me to join her group, which were the WAFS. Women's Air Ferrying Service. I went down to Wilmington right away on the train. She turned me down because I didn't have twin-engine time. I was so disappointed, I went back to Philadelphia. By then my husband had gone overseas again, so I was sitting thinking, I can't go back to Honolulu because I couldn't go because of the restrictions during the war, didn't know what I was going to do. Suddenly I got a call from Jackie Cochran, who heard Nancy Love had started this. Jackie came back from England and said to him, you promised this to me if you were going to use women. She pushed Nancy out of the way and took over. Jackie called me and asked me to be in her first class, called the Guinea Pig Class, even though we had to have 500 hours to get in they weren't sure women could learn to fly military planes. We went down to Houston and later I graduated at Ellington Field in Houston. But for the first two or three months they watched us like hawks and they took all the -- commandeered all the civilian planes, Fairchild 24s, things like that, and they painted them olive drab and put stars on them. Each day we flew a different plane. After a month or so they thought, these girls are going to be able to fly military planes, so they brought in the regular military planes.

Ted Simons: As far as training in Houston and just training sessions in particular, or in generally should say, did you run into rough weather? Did you run into rough planes? Sounds like it was pretty much catch as catch can.

Betty Blake: It was. It was. We did have some bad weather down there of, which they do have in Houston sometimes, coming in off the gulf. We didn't have a lot of it, though. But we had all of the men pilots at Ellington Field were watching us like hawks because -- if one of the girls did anything wrong it was back to the base before you could get back there because these guys were a little bit envious and also our ground crews that were servicing our planes were pilots that had gone to flight school, military flight school and washed out. So they were mechanics on the ground. They watched us like hawks too because I couldn't blame them. They were very envious of us flying these good airplanes.

Ted Simons: I'll bet. What were your responsibilities? Once you got in and proved your mettle.

Betty Blake: I was in the first class, so at graduation they gave us choices. We could tow targets, which didn't sound interesting to me, I didn't want people shooting and maybe hitting my plane by mistake, but we could tow targets, teach cadets, or join the ferry command, the air transport command. I picked the air transport command. We had a choice of the first class had a choice of bases, Dallas, Wilmington, Delaware, someplace near Chicago -- I can't think now where it was, a base there, or Long Beach, California. Well, I figured if I went to Long Beach maybe I would get home to Honolulu. So I asked for Long Beach. That was a good choice because there were so many aircraft factories up and down the coast that three of us, the first three, got checked out in so many different military planes that other girls didn't have a chance to fly.

Ted Simons: What was your favorite?

Betty Blake: B51.

Ted Simons: How come?

Betty Blake: It just purred. I love the Merlin engine. When I was checked out in it, the factory was there at the L.A. airport. I flew three a week frequently to Newark, New Jersey, where they sprayed them with plastic, they called it pick willing them, took the wings off, put them on carriers and took them to England.

Ted Simons: These were relatively new planes?

Betty Blake: Brand new.

Ted Simons: That's got to be a little unnerving.

Betty Blake: At the base, at the North American factory, they had two test pilots, and 44 planes a day came off the assembly line ready to be flown away. The test pilots I got to know them, they were supposed -- form 1 that showed the record for the flying time in a plane. The form 1 would show they had been tested for 20 minutes. The pilots told me they never flew them in the air at all. There were so many coming off every day and there were only two test pilots, all they did was taxi them out and run them five minutes or so and turn them off.

Ted Simons: But you flew them and you loved them.

Betty Blake: I loved them. I always said a prayer the first takeoff because they had never been in the air. I was afraid somebody had left some Sand in the gas tank or forgotten to put some of the rivets in or something. But I never had any trouble. But on takeoff we were always taking off toward these pumping oil wells. I always said a prayer that I wouldn't have to bail out and have my parachute hang up on an oil well.

Ted Simons: Thank you so much for joining us.

Betty Blake: You're very welcome.

Ted Simons: That's it for this special Veterans' Day edition of "Arizona Horizon." I'm Ted Simons. Thank you so much for joining us. You have a great evening.