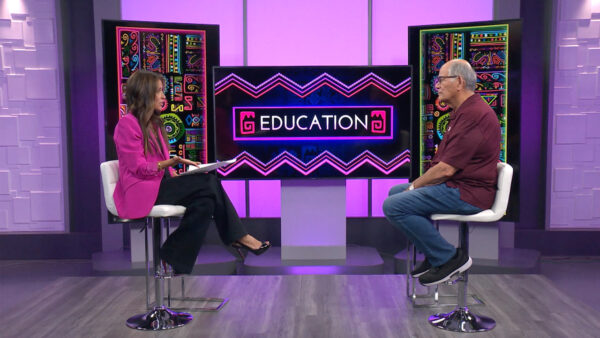

Dr. Vanessa Davidson, curator of Latin American Art for the Phoenix Art Museum, talks about Antonio Berni: Juanito and Ramona, an exhibit featuring work by artist Antonio Berni. The exhibit is the first retrospective of Berni and was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston in collaboration with the Malba-Fundación Costantini in Buenos Aires.

José Cárdenas: The latest exhibition at Phoenix Art Museum, "Antonio Berni: Juanito and Ramona," opened in June and features over 100 objects by artist Antonio Berni. The works include a variety of media including paintings, sculptures, sketchbooks, and more. Joining me to talk about this exhibition is Dr. Vanessa Davidson, curator of Latin American art for the Phoenix Art Museum. Dr. Davidson, thanks for joining us to talk about this very, very fascinating artist, regarded as one of the premier artists in Latin America of the 20th century. Before we talk about why he obtained that fame, give us some background on him.

Vanessa Davidson: Antonio Berni was a very precocious artist and he had a long and very prolific career. He was born in 1905 in Rosario, Argentina. And in 1926, we already find him in Paris at the age of 21, where he developed a surrealist style. Of course, surrealism was all the rage in Paris in the late 1920s, early 30s. He returns to Argentina in 1931, and because of his socio-political proclivities, he decides to embrace the style of social realism. And he rises to some prominence in this painting style throughout the 30s, 40s and into the 50s, but in the late 1950s, motivated by the social distress he saw around him in Buenos Aires -- because of the poverty, extreme socio-economic disparities and socio-political upheavals, he decides to abandon painting for a more visceral medium, and that's assemblage. In case you're not familiar with the term ‘assemblage,' the way I like to think about it is really collage in three dimensions. So in embarking on these assemblage works, he also does a very ingenious thing. He invents two fictional characters and uses them as narrative devices through which to tell the tale of his country's plight. The two characters are Juanito Laguna and Ramona Montiel. And he envisions Juanito as a young boy from the countryside who moves to Buenos Aires in search of work and ends up living in the misery towns or the shanty towns on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. On the other hand, Ramona Montiel is a working-class seamstress who is lured into the life of high-society prostitution by the promise of expensive gifts and a life of luxurious decadence.

José Cárdenas: And we've got some images we're going to show in a little bit to illustrate what he was doing with these two characters. Before we do that, he's regarded not only as the greatest Argentinean artist of his time, but one of the greats in Latin America. Why such fame?

Vanessa Davidson: Well, I think there are a number of reasons. One thing that makes the exhibition that's presently at the Phoenix Art Museum so important is that in this series, Juanito and Ramona, what he does is very compelling in terms of the way he pairs his subject and his materials. So what he decides to do in these assemblages and these prints is to use materials from the fictional world that each character inhabits to illustrate that world. So for Juanito, he uses the trash and metal siding and cardboard and discarded wood that one finds littering the slums in Buenos Aires.

José Cárdenas: And as we're talking about, let's see if we can bring some of those pictures up to illustrate what we're talking about. But go ahead.

Vanessa Davidson: And for Ramona, on the other hand, as this image very well illustrates, he uses old machine parts and toys, old discarded clothing and shoes. This image is called "Juanito va a la ciudad" or "Juanito goes to the city," and it really narrates Juanito's transference from the chaotic jungle, very untidy life in the slums, going to the city reproduced here with buildings and grid formats. And as you see, the swirling clouds above are made from corrugated metal. That image was from 1963. And this image is from 1978. It's called "Juanito ciruja" or "Juanito the scavenger" and what's so interesting about this image as compared to the previous one is the operative shift we see here between the ways that Berni is actually using the collage elements, whereas before, he had these jumbles of discarded detritus, here most of the elements feature corporate brands. So this is one way that he was eluding to the effect of commercialization on the culture of Argentina on the time.

José Cárdenas: And the other thing that one notices is that the image of Juanito changes.

Vanessa Davidson: Yes, indeed. He referred to Juanito and Ramonas as "archetypes of the Argentine and Latin American reality." So as you'll see throughout the exhibition, their facial features change. They're not always depicted in the same way. And in fact, Berni also wrote of Juanito that he could have been a boy from Caracas or Santiago or from Sao Paulo. He could have been a boy from any of the slums of those teaming metropolises. And in this way, although his characters are rooted in the urban milieu of Buenos Aires, their plight is also one that's shared by other similar Juanitos and Ramonas throughout Latin America during this time.

José Cárdenas: Another image that flashed up on the screen, we'll get it back, is one that reflects, if I understand, the dreams that Juanito -- or nightmares would be a better term.

Vanessa Davidson: These are the monstrous, the monsters, they're from a series called the Cosmic Monsters that Berni created in 1964 and 1965. And yes, they illustrate the characters who haunt Juanito and Ramona's nightmares. And as you see in this image, we actually have three monsters in the exhibition. We're very lucky to have them because, as you can tell from the image, they're very fragile and don't travel all that often. But this one is called "Sordidness" or "La sordidez." It's from 1964, and it's created, not only of discarded wood and paper mache, but also a whole tree root system, bottle caps, old camera flashes are the eyeballs. Nails stick out from the jowls. It's just an illustration of what an awesome assemblage artist Berni was.

José Cárdenas: And we've been talking about her a lot, but you also have the images up next of Ramona.

Vanessa Davidson: Yes, indeed. As I was saying before, he uses the materials from each character's universe to illustrate them in his work. So for Ramona's universe he used lace and buttons from her life as a seamstress --

José Cárdenas: She almost looks like an Egyptian goddess in this image.

Vanessa Davidson: She almost does, yes. And as you'll notice, her necklace is composed of keys, of house keys. So he used different -- also with Ramona different discarded industrial materials, but also in the assemblages for Ramona, he used second-hand clothing of the Belle Époque in Paris, he scoured the flea markets for gaudy rhinestone jewelry to dress her up. What's so interesting about this image of Ramona, this is called "Ramona en la calle" or "Ramona in the street" of 1964, and here we see Ramona with her head literally occupied by an image of a politician and by consumer media. These are what you see atop her head there are advertisements for a razor. So he's also commenting as I said before with Juanito he used the corporate brands, the corporate logos and with Ramona he's looking at this culture of consumerism through the images that he puts into her head.

José Cárdenas: And why is she presented not simply as a lady of high society, but a high society prostitute?

Vanessa Davidson: Well, I think he wanted to show the plight that unmarried women faced in Argentina during this time. Women who were not married and didn't have a husband and children had to fend for themselves and the story of Ramona, the arc of the story is she worked for many years as a seamstress, but simply couldn't make ends meet, so that's why I believe he wanted to show how she was not a woman of lax morals, but instead aspired to a better life and much as the imagery in the exhibition also goes to show that aspiration toward a better life was in part fueled by the consumer culture that she was taking in through television and other media ads.

José Cárdenas: And I think we have another image that we're going to put of her up on the screen. This one, what is the significance here?

Vanessa Davidson: This one is one of the most iconic images of Ramona. It's called "Ramona vive su vida" or "Ramona lives her life." As you can see, the dress is made of doilies that would be found in any household. The breasts are made up of gaskets that would go in cylinders for engines. The significance of this work with her arms raised high above her head in an jubilant, independent pose. This is Ramona living her life. This is Ramona who is in charge of her own destiny now that she is a high-society courtesan.

José Cárdenas: Now, you've made a few comments indicating that we're pretty lucky to have this exhibition here in Phoenix.

Vanessa Davidson: Indeed.

José Cárdenas: As I understand it only one of two U.S. cities in which this is being shown. How did that happen?

Vanessa Davidson: This exhibition was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires. Plans for the exhibition began in 2007, and it came to us by a confluence of contacts and very good fortune. I'm very good friends with the assistant curator at Houston Michael Wellen, and we were discussing the exhibition, and I asked if it was travelling. He said, yes, it's going to Buenos Aires and Mexico City and I said how about Phoenix? And he said he hadn't considered that possibility, and I said well let's consider it, so we started to plan out and realized that the dates corresponded and thanks to very, very generous support by the Diane and Bruce Halle Foundation as well as Cox Communications we were able to bring it here. As you said, only the second venue in the United States for the entire exhibition.

José Cárdenas: And how long is it going to run?

Vanessa Davidson: It will be open until September 21st.

José Cárdenas: When people go, because it's an extensive collection, what will they see? You had told me when we were off camera that, for example, the pictures we arranged were kind of in the order that people will see them, Juanito, the monsters and then Ramona.

Vanessa Davidson: Yes, and there are about 32 assemblages in the show, but there are about 42 prints, and printmaking activity was very important for Berni. He was an incredibly innovative and original printmaker. He actually coined two terms: xylo-collage and xylo-collage relief. He applied the same technique of assemblage to wood block printing surface. So, he would create these wood blocks upon which he would incise beautiful imagery, and then he would collage some of the same elements that we've been seeing repeatedly -- machine parts, cogs and wheels and keys and coins to create collages with very high relief. So our visitors will be able to enjoy not only the assemblages, but also a wonderful number of these prints along with 15 of their printing plates which are displayed next to the work. We have the positive and the negative of the image, which sheds light on the artists' creative process.

José Cárdenas: This is very special in so many different ways. Thank you so much for joining us tonight to talk about it.

Dr. Vanessa Davidson:Curator of Latin American Art, Phoenix Art Museum;