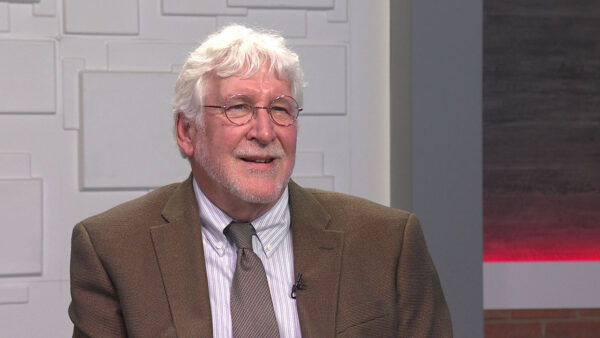

Each year, Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication honors an outstanding journalist with the Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence. This year’s honoree was longtime NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw. In this special edition of HORIZON, we feature Brokaw’s recent speech at the awards luncheon at the Arizona Biltmore.

Michael Grant:

Good evening. I'm Michael Grant. Welcome to this special edition of Horizon. Each year the Arizona State University School of Journalism and Mass Communication honors a leader in journalism with the Walter Cronkite award for excellence. The honor this year goes to the longtime anchor of NBC nightly news, Tom Brokaw. That luncheon was held recently at the Arizona Biltmore. We begin with Brokaw's acceptance of the award and his entire presentation. Enjoy. [applause]

Tom Brokaw:

Thank you.

Tom Brokaw:

Oh, boy. Now, you sit down because it's my turn.

Walter Cronkite:

thank you. [laughter]

Tom Brokaw:

I can't tell you how much it means to me to have this award with this man's name attached to it. He's a towering figure not just in American journalism but in American life. He is the personification of integrity and public service and energy. And he is a model for all of us, not just in my generation but of the generation coming up as well. So Walter, thank you all very much for this great honor. And for the privilege of calling you friend. That means as much to me as anything. [applause]

Tom Brokaw:

I must tell you, both Walter and I are a little relieved, however, to be on this stage. We were both terrified that as we walked up here Manny Molina would call out "hen, hen" instead of "rooster rooster" but it worked out fairly well. I want to offer a special greetings to the honorable governor of the state of Arizona, Janet Napolitano. [applause]

Tom Brokaw:

Who just managed to squeak by a 2-to-1 margin in the recent election. Wish she'd been running against J.D. Hayworth, maybe he would not be calling for a recount now. [laughter]

Tom Brokaw:

I must tell you just for a moment a little bit of what it's like to have been in the same universe with Walter Cronkite. Shortly after I became anchor of the NBC nightly news I was in Israel and I was down in the disputed section of the Sinai that Israelis were giving back to the Egyptians. But there was a holdout group down there that had formed a village, a settlement called Yamit. These were extremely orthodox jews and theh had holed up and they were not going to move. I went down in an effort to get an interview with them. And they had established effectively a bunker and they were heavily armed so you couldn't even approach. But I found a man in a small store not too far from where they were who had radio contact with him. And he had lived in America so he knew who I was. And he offered to be my intermediary. So he got on the radio and in Hebrew began to explain there was this American journalist there who wanted to interview them. Then the people in the bunker would respond via radio in Hebrew and they would translate for me. And they would say, "who is this man?" and he would then transmit back to them, and in this case he greatly exaggerated in an effort to sell who I was by saying, "his name is Tom Brokaw. He is now the most important journalist in America. There was a small pause at the other end and I heard this question come back in Hebrew. And the store keeper looked at me and smiled and he said, "they want to know, are you as important as Walter Cronkite." [laughter]

Tom Brokaw:

So even in remote corners of the Sinai desert. Walter and I have a couple of stories that we share about what it's like to be in this unusual position of being retired anchormen. He was at Yellowstone national park a couple of years ago. He was in line at the gift shop and there was a woman standing behind him. And she was watching with great curiosity this man who was getting ready to purchase something. And finally she couldn't contain herself any longer and she tapped him on the shoulder and said, "Has anyone ever told you look just like Walter Cronkite did before he died?" [laughter]

Tom Brokaw:

And then I'm not sure if this is a truly accurate version of the story but it's the one I like and it's the one I'm going to continue to tell. She turned to Betsy Cronkite, Walter's late beloved wife who always knew just how to keep everything in perspective. The woman, not knowing who she was and said to Betsy, "Walter Cronkite is dead, isn't he?" and Betsy looked off for a moment and said, "you know, if he isn't by now he probably ought to be." in my case shortly before I was to step down from nightly news a decision I made about a year before. My wife and I were up for dinner a year ago at a new restaurant, And she had almost never weighed in on my career decisions because she was so busy with her own very successful professional life. But that night she said, "you know, I wonder if you've thought through all the consequences of this. You've gotten used to being the NBC nightly anchormen and all that comes with it. Getting good theater tickets, sporting events, pick up the phone and get a hold of most anyone you want. That's going to go away." and I said, "you know, with typical anchorman humorous, I don't think so, Meredith. I think I've built up enough momentum at this stage in my career that there will still be people who will pick up the phone." she said, "I don't think you can't count on that, Yom." just then the waiter came over and he was gushing with emotion, well he's making my case. He leaned over and said, "we're so excited you're here tonight" he said. "it's a new restaurant and you chose to come in here. I went back to the kitchen and told the staff, they're standing at the doorways of the window there. Because, Mr. Koppel, we never miss "nightline."

Tom Brokaw:

Meredith leaned back and said, good luck, Mr. Koppel, with your new career.

Tom Brokaw:

I want to take a few moments if I can of your time and express in the most heart-felt grad Tuesday for being with you in this city, this great part of the defining geography in the southwest. In phoenix and throughout Arizona. And to see the great diversity in this audience as well and to be a part of this important new school and to be with my friend Walter. It is, for me, a rare moment. It's the kind of moment that when you grow up in the working class environment as I did you never fully get used to. But I also want you to remember this: while we're here enjoying good fellowship, secure in one of America's great cities, at this hour young men and women from Arizona and across this country are in distant and dangerous places. They're dressed differently than we are. They're in camo wear and kevlar and steel-plated boots and heavily armed. They're on duty in lands where they don't speak the language and the enemy doesn't wear a uniform or hesitate to seek cover in sacred places or civilian homes as they plot their ever more deadly attacks against the American men and women who have volunteered for this terrifying mission. These young men and women have sworn to sacrifice their lives and their limbs to defend this country and each of us. Their families live in a state of perpetual fear that next call or knock at the door will bring unbearable news. They're proud and patriotic fellow citizens who do this dangerous duty for modest wages and for a very high price. About ten days ago I was back at Walter Reed again. And I was going from room to room in the amputation ward and then down to the therapy ward. Meeting the young men and women who were missing legs, and arms, recovering from crushed skulls and multiple gunshot wounds. Not one of them had more than a high school education. Not one of them came from a town large enough for you to recognize. Not one of them came from any other kind of family except the working class family. Their wives and their parents sat stoically in their rooms offering comfort and concern, anxious, proud, but a little confused about how this came to be. However you feel about the decision that put these young men and women in harm's way, supportive, ambivalent or as more people are every day, angry, we must not forget they are where they are so we can be where we are. We owe their families at the very least recognition of their sacrifices and shared concerns. You can hate the war, but you must honor the warrior. For no nation should be divided between those in uniform and those not, between those who send their sons and daughters to war and those who have now the privilege of not doing that. It's an unacceptable condition, politically, culturally, morally, especially in a democratic republic. Very little is being asked of each of us, and so much of them. They're serving in a war where so much has gone wrong, and yet where there has been so much individual heroic, noble action, a war that began with a strong common determination is now a war on many fronts, there and at home. In this election season especially, we should remind each other of our obligations to be stewards of what they defend and what we have allowed in too many instances to be devalued, our national political arena. This election was a defining moment in the early stages of the 21st century. But it was only the beginning of a process that has yet to be resolved. There were some heartening signs, however you feel about the outcome. For me the heartening signs were that people were making judgments based not on political theology, for the polarization of political ideology, but on what they thought was best for the country. The democrats won this time. The republicans may win the next time. If both parties learn that this country wants to move forward together, it does not want to have a political culture of blame, it wants to have a political culture of responsibility and solution. I often use your governor as an example when I go around the country. Democratic governor in a red state. Kathy Sibelius in Kansas, democratic governor in another red state. Brian Switzer in Montana democratic governor in a red state. George Pitacki republican governor in a blue state. Mitt Romney, the conservative member of the LDS and a republican governor of the most blue state that we have, Massachusetts. This country longs to move together on a common plain. The challenges are great. I have a concern, a special concern about the effect of all this on a new generation of young Americans coming of age with the power of a transformational technology at their fingertips. They have search engines and p.d.a.'s and cell phones and my space and you tube. They have bloggers that blabber and bloggers that enlighten. All that breathtaking change in how we communicate, do research, and conduct business entertain and inform each other journalistically is happening at warp speed. It is seductive. And it has anchored a new generation to a keyboard and to a virtual life. I like to remind those young people at the keyboard that at the turn of the last century another generation of Americans was excited about the empowering technology of their time. Think about it. The turn of the 20th century, flight, travel, telephone, the arrival of the automobile. And yet the 20th century was one of the deadliest in the history of mankind with two world wars, Holocaust in Europe and southeast Asia, the introduction of a nuclear age, new plagues even as the code of life was being cracked. We live in a world of unexpected consequences in which genocide and ancient hatreds are not eliminated by delete buttons, in which climate change is not reversed by hitting back space. In which answers to global poverty or global economic competition cannot be found on the tool bar under the heading "help." that's why journalism is so important, and all the old-fashioned virtues of the man that you honor every day by putting his name on your school. When I'm asked about the most memorable personalities that I've encountered in more than 40 years of journalism I think most of you expect me to saw some of those you saw on the screen. Gorbachev, nelson Mandela, Robert Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Dr. Martin Luther king Jr., Mick Jagger, Bruce Springsteen. Instead I describe the brave young Americans, black and white, on the streets and the dirt roads of the American south, in the 60's who were fighting for civil rights at the risk to their lives. I remember those who said that they were morally unable to fight in Vietnam and were prepared to pay the consequences of that, and those who said "I will serve my country" and raise their hand and put on the uniform and went to Vietnam. I remember a young American surgeon in Somalia late at night in a tent operating to save a child whose name he did not know, describing to me the mountain of medical school debt that he still had to pay off. But he thought if god had given him the skills, he owed it to his fellow man, wherever they were in the world, to try to save their lives. A Mongolian the tribesmen describing to me in the remote reaches of that country how he rode his horse 20-miles through a blizzard to cast his first vote. And when he wanted to know what the winter temperatures were in Montana where I spend a lot of time I told him, sometimes 20-degrees below zero. And he looked at me and said, "is that all?" young and old of every human origin, connected to a website of their personal convictions, they put their boots on the ground, they put their hands in the dirt, they spend nights in scary places to make the world a better place. In March of this year I was in Pakistan, Kashmir covering the affects of that devastating earthquake in which 80,000 people were killed. And I thought myself as I prepared to bunk down in a cargo container, I'm not sure this is exactly what I had in mind when I left nightly news. A suite at the four seasons was what I had conjured up. But I awoke the next morning at dawn and had coffee with three young American aid workers standing out at this bleak outpost. And within an hour I knew I had made the right decision, because my whole sense of this generation had been renewed once again. They were funny and self-deprecating and they had been there for three months. Trying to put Pakistan back together brick by brick, village by village, they know that we live in a smaller planet, with more people, many of them on the move in a desperate search for economic opportunity or to escape political oppression, a world of ever diminishing natural resources especially energy resources, a world in which a colossus is rising in the east. A world in which rogue nations have learned that nuclear weapons can be a ticket to the big table. We live at the apogee of western civilization and in despair that ancient sectarian rivalries are lethal alternatives to modernity and reason, a world of a rapidly expanding population of Muslims who have a love-hate affair with America, tilting heavily toward hate these days. They envy our successes. They disdain our pluralism. They're enraged by what they believe is our sense of entitlement. Young Muslims who live in politically and economically oppressive regimes where they are easy prey for Moulahs who teach them that to hate America and do violence to it is a matter of faith. We can't ignore them. And as the last four years have demonstrated in tragic fashion a military response is only part of the equation. If that rage and that hostility is not addressed in a more effective fashion I believe we are all condemned to live in a state of perpetual terror, in the west and in the Islamic world. To do that requires the best thinking of all of us and a personal commitment of all of us. It's time to remember the legacy of what I called the greatest generation, the young men and women who came of age in this country during the Great Depression, when life every day in the most personal, possible fashion was about deprivation and sacrifice, about learning to live without and to share what you have. And just when there was some hope that was coming to an end, that generation was summoned to fight the greatest war in the history of mankind. A hand-to-hand struggle, really, on six of the seven continents in all the skies and all the seas throughout the world. And when it was over freedom had won but the price was terrible, 50 million people had perished. Yet this generation came rushing home to go to college in record numbers, to build new industries, make new scientific discoveries, give us new art and new communities, to marry in record numbers, to expand the freedoms of those left behind for too long, and to do something unprecedented in warfare, to rebuild their enemies, to never stop giving back. They understood that patriotism was not a loyalty oath, it was the understanding that patriotism means to love your country, but to always think it can do better. It can be improved. To have the courage to step out and say, "can't we do better?" to become involved in the great discussions and the issues of the day. It would have been easy enough for the members of the greatest generation who have returned from that war -- and Walter was one of them, by the way -- to have put down their weapons and to have said, "I've done my share. I grew up in the great depression. I fought this war. I gave the world the freedom it now enjoys. I'm going home and I'm worrying only about me." but they did not. One of my very favorite stories that grew out of my association with this generation came after the book was written, to my regret, and it was typical of the humility of the people that I wrote about and their modesty. One of the principles in the book came to me and said" it was a story I didn't tell you." and I said, "well thanks a lot for telling me now." he said, "I was gravely wounded in Italy. They thought I was going to die before they got me down the mountainside then they thought I would be paralyzed for life "this was a man who grew up in rural Kansas when his family rented out the two floors above the basement during The Depression so they could make ends meet while living in the base, he was when you see the pictures of that time a real Adonis, a three sport athlete at the University of Kansas. But he enrolled, enlisted in the tenth mountain division and then was grievously wounded. And he was shipped back to a veterans' hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. And the bed next to him was a young man he'd never met before who served in a different outfit in Italy, the 442. He happened to be Japanese American from Hawaii. When Pearl Harbor happened this young man had rushed down to the harbor to treat his fellow American citizens. The first aid training he had learned in boy scouts. And then he began to hear about his cousins and aunts and uncles being shipped off to internment camps, some here in Arizona. And so he enlisted in the 442nd, an all Japanese American combat brigade that became the most heavily decorated in the southern European theater. And before he left for war, his father said to him, "you may have to die for your country. But if you do, it will be a great honor for your family." He lost an arm in one of the most heroic actions in the European theater in which he almost single-handedly rescued a Texas National Guard outfit. The third bed was a young man of wealth and privilege from Detroit who could have gotten out of combat but he landed on Utah beach and he, too, was severely wounded. And they would lie awake at night, these three new young friends from such different circumstances, and talk about what they were going to do with their lives. And they decided that public service was a most honorable course for all of them. And they had a reunion in the United States senate. Bob Dole, republican of Kansas, Danny Inouye, democrat of Hawaii, and the late Phil Heart known as the conscience of the senate, democrat from Michigan, from whom one of the most prestigious addresses the hart office building is named. At a time when America is determined to advance the principles of democracy around the world, to be a model for advancing the common welfare, it is a paradox for our political system to have been reduced in too many election cycles to a collection of narrow interests across the spectrum, from left to right and back again. What must they think in the world of Al-Jazeera when they see American politics play out on their screens? Or when they realize that a senator from the state of Montana, for example, with a small population, or from the state of Nebraska, goes to Washington and raises his or her hand, accepting the oath of office for one of the highest and most distinctive offices in the history of participatory democracy. That new senator has to go back to his office and remember he has to raise 6 or $7,000 every day for the next six years of his term to run a competitive race. What must they think about that when they see American politics play out? Tough greatness in any nation is not in the economy alone, or in the successes of its individuals, or in the glittering edifices of its cities and states. Our time as citizens and as journalists will be judged by the whole and not just by the parts, by how we nurture the legacy of those who went before us, the greatest generation, that test is within each of us wherever we live, whatever we believe, whatever we do. It is time to re-enlist as citizens. Thank you all very much for this great honor. Thank you. [applause]

Announcer:

Horizon is made possible by contributions from the friends of eight, members of your Arizona PBS station. Thank you.

Tom Brokaw:Longtime anchor NBC Nightly News;