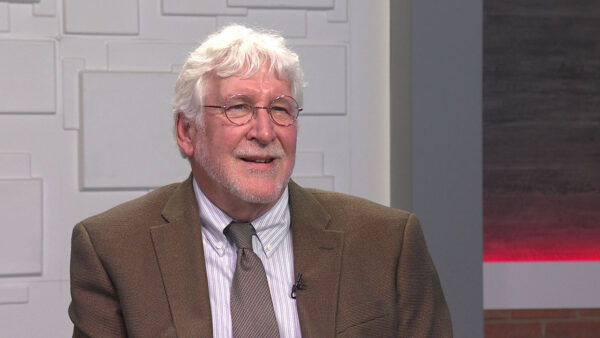

Ted Simons talks with Dr. Bernard Harris, the first African-American to walk in space. Dr. Harris is also the founder of the Harris Foundation, a nonprofit organization that supports math and science education and crime prevention programs for children. The Foundation is co-sponsor of the ExxonMobil Bernard Harris Summer Science Camp taking place at ASU.

Ted Simons: About 50 middle school students are spending two weeks at A.S.U. learning about science and sustainability. They're here for the Exxon Mobil Bernard Harris summer science camp. A doctor and a former astronaut, Harris has spent much of his life encouraging kids to pursue their interests in science. I'll talk with Dr. Harris in a moment, but first, here's an activity that took place earlier today at the camp that's organized by A.S.U.'s Fulton School of Engineering.

Teacher: You will have five minutes to plan.

David Majure: The assignment is simple. Build a raft using foil and straws. Design it to hold as many pennies as possible without sinking.

Student: They need to be --

Bernard Harris: What do you think will happen to the straws --

David Majure: As the kids planned, veteran astronaut, Dr. Bernard Harris watched and offered words of encouragement as he's done many times before. This raft rally activity has become a staple at the summer science camps that take place at 30 universities across the country. This one is coordinated by A.S.U.'s Fulton school of engineering.

Stephen Rippon: This is a great opportunity for us to work with you guys' young minds and really encouraging you to get involved in science and technology and engineering and technology fields.

Bernard Harris: Why is it important for us to emphasize the stem careers -- science and engineering and mathematics? Many years ago we were the leaders, the innovators and creators of most of the patents of the world, and lately, that's not so.

David Majure: All of these kids are attending the two-week camp free of charge for a reason. They've shown an interest and aptitude for science and math. Now it's time to put their skills to the test.

Students: 94, 95, 96 -- wait --

David Majure: Supporting the weight of 133 pennies, we finally have a winner. Of course, all of these kids are winners and if we're lucky, maybe all of us will benefit from their success.

Ted Simons: Joining me now is Dr. Bernard Harris, a veteran astronaut and the first African American to walk in space. Thank you for joining us tonight on "Horizon."

Bernard Harris: Happy to be here.

Ted Simons: I got to ask you, yesterday was the 40th anniversary of the landing and moon walk and all of these things. Where were you when that happened?

Bernard Harris: I wasn't too far from here. I grew up on the Navajo Indian reservation and I got a chance to watch that launch when I was 13 years old right from here and it was amazing.

Ted Simons: It really was. The fact that live television was there and we were all watching it together. When you were 13 and watching that, were you saying I want to do that or were you just saying, neat?

Bernard Harris: When I saw the guys land on the moon, buzz and Neil, they talked about how wonderful it was for this nation and for the world. And to me, I took it all in. I said, you know what? Those guys are doing something I want to do and I think it was at that point that I decided I wanted to be an astronaut. Seriously.

Ted Simons: And you were living on the Navajo reservation?

Bernard Harris: Uh-huh.

Ted Simons: Talk to us about that.

Bernard Harris: I was born in Temple, Texas. I came from a broken home. My mom was an educator and found a job working for the Bureau of Indian affairs. Three kids moved out here and started out in a little place called Greasewood, Arizona, and moved to another part of the reservation.

Ted Simons: How long were you there?

Bernard Harris: Until I was 15 and then moved back to Texas.

Ted Simons: Did you get lasting relationships?

Bernard Harris: I certainly did. I come back and go to the elementary school and speak and the high school. And one of the reasons we wanted to have a camp in this area, at A.S.U., and also one at the University of New Mexico, I wanted to engage the Native American population to math and science education.

Ted Simons: I want to talk more about the camp in a second. Back to you as a youngster saying, that's what I want to do. I wouldn't mind going close to there, if not there. You were also inspired by Star trek.

Bernard Harris: I'm one of the original trekies, or whatever they call it these days. So when I saw Bones, the ship's doctor, run around with these new technologies he used, I got excited about that. It's ironic, a lot of those technologies on Star trek, we're now using today. Walking around with P.D.A.s and with tablets, computers and things like that. And they were using it over 40 years ago.

Ted Simons: And it's fascinating to know -- you knew it was a television show. These were actors and still it was an inspiration.

Bernard Harris: It was. I was one of those kids fascinated with science, especially science fiction and space science in particular. And my -- when I decided to be an astronaut, I had to figure out what type of astronaut I would become and, of course, Bones helped. But the real guy was a name by the name of Joe Kerwin, and he was the first American physician to travel in space and I followed his career and got as close as I could in following in his footsteps.

Ted Simons: You wound out a space walker. You did it. The first African American to walk in space. I know it's a simple question, but what was it like?

Bernard Harris: As an astronaut, we -- the things we want to do, we have two goals, primarily. One is to climb on board a spaceship and get blasted off into space. Which is not a normal thing to do for people. And the second is not only to travel in space, but to walk in space. And I got a chance on the second flight to don a 350-pound spacesuit and walk outside and it was awesome.

Ted Simons: In what way? Out of body, like look at me for a second, I'm out here doing it?

Bernard Harris: The first part is all routine. We have a timeline we have do, you know, there's certain activities we have to do. We deploy the satellite. Did prep work for the international space station and all that was done, we had a chance to sit back and take it in. If I can provide a picture for you, imagine me being on an end of a robotic arm, lifted up about 35 feet looking down at my crew members and behind that is the big blue ball, planet earth and behind that, a sea of stars. It was incredible.

Ted Simons: It sounds spiritual. Did you get a spiritual jolt out of it?

Bernard Harris: I don't think there's an astronaut who didn't come back with some closerness to nature, you know, versus, some people call that god.

Ted Simons: And you now have taken your experience and moved it to summer camps. Talk about the goal you're trying to do here. It sounds like getting kids interested in math and science, how do you do that?

Bernard Harris: You make it exciting. You tell this group of kids that we brought here who have already proven their proficiency and show them how the learning they get in their schools can be applied to anything that we do. Remind them that the cellphones and the televisions and the -- the cellphones and televisions and the cars and video games are all created by scientists and engineers and that scientists and engineers rule the world. I joked with them this morning when I mentioned, I said, I know in your schools some of your classmates may think you're a geek. Well, guess what? Geeks rule the world. It's ok to be smart.

Ted Simons: I notice middle school kids were targeted. That's an important age to get that message across?

Bernard Harris: It really is because they've gotten a certain level of knowledge in elementary school and now getting into middle school where they're getting the real fundamentals of math and science education. If you poll kids at this age group, they're excited about learning and education and particularly math and science, but something happens on the way to high school or in high school, they begin to drop off, that interest. What we're trying to do is ensure them -- give them an extra boost. A booster shot so when they go through middle school and get in high school, that they're really turned on by math and science.

Ted Simons: Do you see yourself in some of these kids?

Bernard Harris: I do. That's the reason I do this. The only reason I'm sitting here having this conversation with you as a physician and an astronaut and venture capitalist is because I decided to get involved in math and science. I chose education as the tool in which I would use to accomplish my dreams and that's what we're trying to do and thank goodness we've got tremendous support from the Exxon Mobil Foundation that allowed us to expand from two camps to 30 camps. So we have 30 around the nation now.

Ted Simons: And we need engineers, we need scientists, if we want to go back to the moon, go further into space, whether it's a space station or mission to Mars. We need these kids to grow up and take us there.

Bernard Harris: We need math and science, the stem education -- science, engineering, and we need kids in this area because it's critical to the survivability in this country. We're not producing enough that are necessary to keep us leaders and if we want to be competitive, it behooves us to be sure that all of our communities have the wherewithal, the talent to accomplish their dreams and again we think that is education.

Ted Simons: Last question. Space program. You like where it's headed right now?

Bernard Harris: Well, I am. I'm especially happy about the latest leader, General Charlie Bolden. I think he'll bring a new initiative to the program. Especially the manned flight program.

Ted Simons: It's a pleasure to have you here. Congratulations on your success and thank you for joining us on "Horizon."

Bernard Harris: My pleasure.

Dr. Bernard Harris:Founder, Harris Foundation;