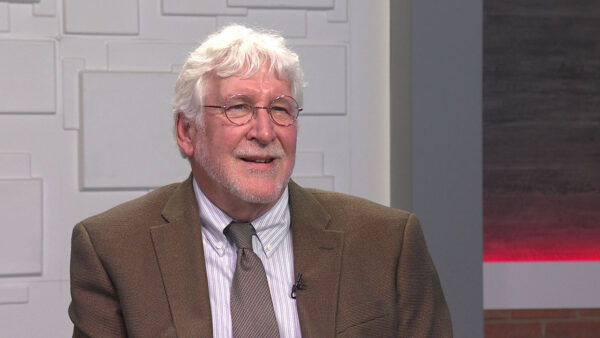

During the recent legislative session, lawmakers made several changes to Arizona’s state employee pension systems. Labor groups have threatened to sue saying some of those changes are unconstitutional. Employment attorney John Balitis shares his legal analysis of whether or not the changes pass constitutional muster.

Ted Simons: State lawmakers made some changes to the state's pension system this last session, some public employee unions, though, think the changes may violate the constitution which says, quote -- public retirement systems shall not be diminished or impaired. Here to talk about all this is John Balitis, she an attorney an employment attorney I should say with Fenimore Craig. Good to see you again. Thanks for joining us. Well alright, the system adjustment the, the retirement system adjustments. Who exactly is affected by these?

John Balitis: All wide variety of people, because it affects the reforms affect four different plans in the state. The adds state retirement system, which is the largest. The correction workers retirement system, the public safety retirement system, as well as the elected officials. You've got state and local government employees, firefighters, police officers, correction officers, and elected officials, which include judiciary members.

Ted Simons: OK. Explain the adjustments.

John Balitis: Well, there is a wide variety of adjustments. They range anywhere from adjusting contribution rates, to cost of living adjustments, to caps on certain enhanced programs. The core adjustments relate to contribution rates. And this is true both on an individual level and on a global level. For example, right now a police officer contributes about 7.5% of his or her wages to their pension fund. Will over the next five years, under the reforms, that's going to creep up. That's going to inch up to about 11.5%. Same is true on the global level with respect to contribution rates. Right now in the Arizona State retirement system, have you a 50/50 ratio between the public employer contributing and the individual. Under the reforms, next month, that will start to change. The employee now is going to be contributing 53%. The public employer will contribute 47%. All these types of changes are designed to promote the financial health of the plans of the systems.

Ted Simons: What about double dipping? That was addressed as well.

John Balitis: Double dipping is a practice that is developed over the years in large part in the teaching segment, and it involves -- but covers all plans, but it involves situations in which an individual will retire, start collecting a pension, but then will go back to work. Sometimes through employment with another agency that then gets paid around the back. And there is a measure within the reform that puts restrictions on double dipping. One of the things that is going to become new in that scenario is, the employee, if they go back to work and continue to collect pension benefits, will then have to start contributing to the plan again. Currently in the double dipping scenario that doesn't happen.

Ted Simons: Interesting. All right, you mentioned enhanced programs, things like, what, lump sum payments? That is adjusted as well.

John Balitis: There's a program for firefighters and police officers, for example, for deferred retirement opportunity program, the drop program. Which in its current form allows a police officer or a firefighter to defer their retirement for five years, and during this five-year period, they are no longer contributing to the enhanced program, which results in a lump sum payment at the end of the five-year period in addition to the regular pension payment that they would receive. These payments are large in some instances, quarter of a million dollars at the end of the drop period. Some of the reforms will address this and then will require contributions during the drop -- during the five-year deferral period, which aren't required now. Once again, trying to promote the financial stability of the plan and infuse more money into the trust and the plan.

Ted Simons: That really is the reason these adjustments are necessary, correct? Talk about these retirement systems, and the ratio of assets to liabilities. Where it has been what it is right now.

John Balitis: Well, these retirement systems have been around since the 1950s, when they were first created. And in the mid- to late 90s they were flush. They were -- their assets exceeded their obligations by maybe 10, 15, 20%. Now, and this is really the catalyst for all of these reforms, the asset to obligation ratio, meaning whether your assets can cover your current obligations, is fluctuating, depending on which of these plans you look at, somewhere between 66 and 80%. By industry standards, a public retirement plan is considered healthy if those assets could support 82-100% of the current obligations. So statistically the plans aren't really currently sustainable, if you look at the statistics.

Ted Simons: And yet you said that in times past, these programs, these systems were flush. Does that not suggest when the good times come back again, which I think we all hope they do, this whole situation becomes more viable?

John Balitis: Absolutely. But we're worried about the sustainability of the plans now. When the economy turns around, we won't be in an asset contraction mode anymore hopefully, we'll be in an asset growth mode. And just like your investments and mine, the plan assets will grow, and we will have a completely different situation. But that doesn't alleviate the need at this point to address what's going on with the plan.

Ted Simons: And in addressing what's going on, a lot of folks are look at the constitution, which and I'll read it again -- public retirement benefits shall not be diminished or impaired. Benefits. Diminished. Impaired. Seems rather clear. Not necessarily?

John Balitis: Well, what you're reading from is article 29 in the Arizona state constitution. And this article was passed in 1998 as a referendum. It was proposition 100 back then. And when it was passed, the plans were flush. And the reason it was passed to protect benefits rights was because there was concern that these funds, these public retirement funds could be rated to support other programs. Or create new programs. And the legislature wanted to protect them. They weren't thinking down the road at the time about the situation we're in now which is exactly the opposite. So these terms benefit, diminish, impair. They're not defined anywhere in the article. People weren't worried about defining them with the idea that at some point we'll have to cut back on benefits. And so we have no definitions for those terms. And that opens up the avenue for a lot of judicial discretion. If and when a lawsuit is filed to challenge the reforms, to interpret the terms and see how they play out.

Ted Simons: If and when a lawsuit is filed, who hears the lawsuit?

John Balitis: Well, that's actually an excellent question. Because depending on what's at issue in the lawsuit, say, for example, the elected officials retirement plan elements in the reforms are at issue. That would affect many sitting judges superior court judges, judges on the court of appeals, Supreme Court judges. All of whom have a personal interest in the outcome of the dispute. We have a rule that takes into account the possibility that this will happen, periodically disputes will arise that could impact a judge personally. The rule is called the rule of necessity. And what the result of necessity basically stands for is the proposition that in this situation, where have you a dispute that could affect sitting judges personally, the outcome could, it gets bumped up to the Arizona Supreme Court. With the thinking that the best and the brightest and the most publicly visible and accountable judges in the state would hear it and decide it. So depending on what's at issue in the lawsuit, will depend on whether it goes to the Supreme Court, or it stays at the trial court level.

Ted Simons: And last question, this of course depending on whether or not the lawsuit is filed, let's say it is filed, let's say parts of it succeed. Not all of it, just parts of it succeed. Does that mean the entire state University system, the entire adjustments that were passed by the legislature sign in addition law, the whole thing is down the tubes, or just that one thing that didn't go through?

John Balitis: The way it should work is this should be like an a la carte menu. When it's challenged, if it ever is. Meaning: let's say the lawsuit is going to take into consideration 12 different reform elements. And six of them passed constitutional muster, because they don't constitute an impairment or diminishment of a benefit, and the rest do not. And they are invalidated. Those invalidated provisions, then, will not move forward as part of the reforms. The remaining ones that passed the test should remain intact and stay in place.

Ted Simons: Should.

John Balitis: Should.

Ted Simons: But not necessarily.

John Balitis: Well, that's the way the legislation is written.

Ted Simons: OK.

John Balitis: So we should not have a situation where one element fails out of a dozen, the whole reform package goes away. That isn't the way it was contemplated.

Ted Simons: All right, very good. Good stuff. Thanks for joining us.

John Balitis: Thank you, Ted.

John Balitis: Employment attorney