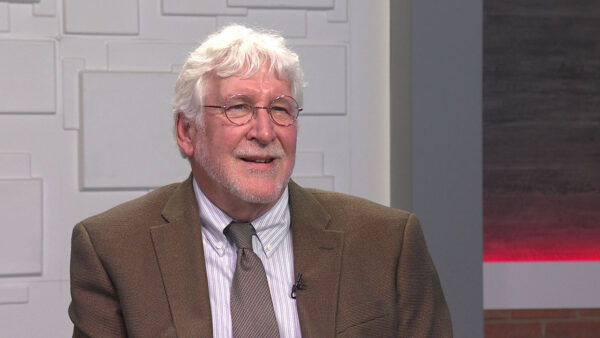

The United States Supreme Court’s new session started October 6. Arizona State University law professor Paul Bender will discuss the important cases before the court, including an Arizona case involving the drawing of congressional district maps.

Ted Simons: Good evening, and welcome to "Arizona Horizon," I'm Ted Simons. The U.S. Supreme Court's new session is underway and the assembled justices wasted no time in reshaping the debate over same-sex marriage. The High Court is set to take up a variety of cases this session along with two from Arizona. Joining us is ASU law professor Paul Bender.

Paul Bender: Always eventful, but not as eventful as people thought it was going to be. Almost everybody thought they were going take one of the gay marriage cases. That would have been the signature event of the term, and it probably wouldn't have decided until the end of the term, but they decided not to grant certiorari.

Ted Simons: Why did they do that?

Paul Bender: When you're thinking about that, you should bear in mind what the result or effect of them denying cert in those five cases, they have put on hold decisions permitting them to go forward in those states. As soon as they denied cert they knew gay marriage was going to expand pretty dramatically to all the states in those three circuits. That's a lot of states. So can you do that and still think there's a possibility that you would ultimately hold that it's constitutional to ban gay marriage? By the time they get around to it now, it'll be a year or two from now, 90% of the country will live in states that permit gay marriage. So I view that denial as basically raising the white flag by the people who are opposed to gay marriage. We know there are four people on the court who think it's constitutional to ban gay marriage. Scalia, Roberts, Alito and Thomas. They could have granted cert but they didn't. Why not? Because they don't have the fifth vote. If they don't have the fifth vote now, when will they have a fifth vote?

Ted Simons: And it had to be Kennedy, yet Kennedy went ahead and temporarily blocked. What did he do and why did he do it?

Paul Bender: I think that makes sense. There's no circuit split. That's the one time the Court will have to take that case. The ninth circuit held the way the other circuits held that, bans on gay marriage are unconstitutional. But the losing parties in those two states can go to the full ninth circuit and asked for an en banc review. If they held gay marriages are constitutional, then there will be a split in the circuits. I think it makes sense for Kennedy to give them time to ask the circuit whether they want to take the case. I think it would make sense to hold up until they decide. You don't want people getting married and a year later, hey, those marriages are invalid. That would be just terrible. It makes sense to me to have him give a statement, to give them time to go to the ninth circuit. To give them time to file a cert decision just doesn't make sense. I assume that's what he's doing. He's giving them enough time to file a rehearing en banc petition before the 9th Circuit. If the 9th Circuit was to take this case, they can take it without the decision going into effect.

Ted Simons: Have they refiled? Do we know what the 9th Circuit is going to do?

Paul Bender: I think they have already asked, but they haven't done anything and probably won't for a while. To grant a hearing en banc you need all of the judges in the Circuit in majority. They pick 11 judges out of the 20-odd that they have and those 11 could be tilted one way or another, it's all random. It's not inconceivable that the 9th Circuit would grant the hearing, reverse the decision, and uphold the bans on gay marriage. If they did that, the Supreme Court would have to take the case. But that'll be a year from now, and meanwhile gay marriage will be the law in all those states and the circuits they just denied cert on the other day.

Ted Simons: And it seems like we kind of know what the Court is going to do.

Paul Bender: You would think so. It's hard to imagine one of those people like Kennedy changing his mind in the next couple of years. Why would you do that, if he didn't do it now?

Ted Simons: Very quickly, how unusual for a single justice to put a temporary block on something?

Paul Bender: That's common, just for a couple days before he can give it over to the full court. There's a conference tomorrow and I assume Kennedy will present the application for the stay. If the court gives a stay, what are they saying? Unless it's just a stay to go to the 9th Circuit and ask for a rehearing en banc. They could give a cert petition. If they give a stay just for the purpose of a rehearing petition, I don't think that means anything. They are giving them a chance to create a cert conflict. Why would people want to create a conflict to grant cert so they would then lose?

Ted Simons: Would they just want to have it heard?

Paul Bender: Why? It would make no sense for them. They will get an opinion about gay marriage and the due process generally, the protection clause generally, it could be a very broad individual rights opinion. Kennedy a would write it. He would assign it to himself and you can never tell what Kennedy will do. I would think -- they have lost this battle, I think they realize. And I would think they would just forget it now.

Ted Simons: The time is long gone for sending a message, in other words.

Paul Bender: Right, yeah.

Ted Simons: Let's get to Arizona cases. The Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, this case now the legislature challenging. Give us an example of what's going on and why the court is deciding to get involved.

Paul Bender: That's a very good question. What's going on, the people of Arizona in 2000 adopted a constitutional amendment to take redistricting of both state legislative and congressional districts away from the legislature and give it to the Independent Redistricting Commission. And they have now done the independent commissions has done it twice. And the second time was after the 2010 census. And that -- that guided what happened in 2012 elections. Well, 2012 elections, five of the nine congressional seats in Arizona are Democratic. I think the Republican legislation saw that coming and fault the Independent Redistricting Commission. They didn't like what they did so they are trying to get that changed. What they have done is they have brought a suit saying it's unconstitutional for a state to have redistricting done by an independent commission. And I would have thought that the Court would say, we've already said in two or three cases that states have a lot of freedom in how they redistrict. There's no conflict in the circuits. Independent redistricting commissions are the wave of the future. More and more states are doing it. It's thought to be a good government thing. It's hard to argue against it, except for partisan political reasons. Why the court would want to jump into that is very difficult for me to understand.

Ted Simons: Isn't the argument that the United States Constitution gives power to draw these districts to the "legislature"?

Paul Bender: But what does that mean? Can the governor veto redistricting? Can the legislature give it to -- if the legislature is redistricting, the people take out a referendum on that? The Court has already said both of those things can be done. If you're going to give the Governor that much power and let the people overturn what the legislature does, then you're not just giving it to the legislature. And it's hard to think why the people who framed the U.S. Constitution in 1787, would have wanted to say to the states, you district, but you've got to do it in a certain way that your formal legislature. What would be the reason for that? It's hard for me to see what the reason would be for the court to take the case to, stir things up. If they were to strike down the Arizona Redistricting Commission that would put a stop to what I think most people in politics think is a really good development. And that is to get redistricting out of the partisan arena. We know what legislatures do when they redistrict. The first thing they do is save their own seats. And then they gerrymander to maximize the strength of their pretty. That's not a very Democratic thing to do.

Ted Simons: The question is, is the commission allowed under the Constitution, under federal law. You're saying that the precedent says --

Paul Bender: There's precedent on the commission's side but there is language that's difficult to overcome. By the legislature thereof. The question is by the legislature thereof mean? The most natural think I think it for to mean is by the normal legislative process of the state, whatever that is. They meant to say they do it the way you do legislation. They meant to say don't have the governor do it. That is why they said legislature. Otherwise do whatever you do. That's the language in the old cases that uphold letting the Governor veto and letting it be a referendum, say that's the normal legislative process, and that's okay. And that makes sense. What the framers were doing there was to say states should draw the districts unless Congress wants to take it over. If you say the states should draw the districts, why shouldn't it be up to the states to decide how they are going to do it? Why would the Constitution of the United States stop the people of the state from saying how they want to district their states?

Ted Simons: You're saying if people say we wants a committee do it, that falls under the umbrella?

Paul Bender: Exactly. It would be especially ironic to the Supreme Court to say the people cannot get districting congressional seats away from the legislature, but they can get redistricting the legislature away from the legislature. There's nothing in the Constitution to stop that. It doesn't make any sense.

Ted Simons: Any idea where the Court's going to go on this?

Paul Bender: The fact that they took it creates doubt in my mind. They didn't have to. When I think about it I say to myself, is it really plausible they will stand in the way of this development nationwide to get redistricting out of the partisan arena? It troubles me, because it's one of several things the Court's done recently that really seem to be done for partisan political reasons. That is Republicans versus Democrats, rather than for principle reasons. There were cases last week where they stopped voting changes for going through, which were going help minorities in voting which the Republicans were against and Democrats were for. The court gave stays to keep the thing the way Republicans want it. If that's done for political reasons that's very unfortunate.

Ted Simons: Two Arizona cases this session.

Paul Bender: Yes.

Ted Simons: The other is involving a church sign ordinance in Gilbert. The idea of a city or town being able to put into ordinance nonprofit signs, you can't do this, you can't do that. This has made it to the Supreme Court.

Paul Bender: That's also surprising. But it's there for a technical reason that's important. In the law of the First Amendment, the doctrine makes a difference that when you restrict speech you do it on the basis of content. If it's content based you need a compelling interest and it has to be narrow. If it's content neutral the state has a lot of latitude. The question is there's 19 different kinds of signs that you can put up in Gilbert without a permit. The church comes under temporary events signs. Those have to be I think six square feet maximum, and they can only be put up for a day before the event, they have to be taken down right after the event. Political signs for political candidates can be 32 square feet and they can approximate up unlimited time before the election. So the argument is, hey, that's a discrimination against the church's signs. If it's a content discrimination, the City has to show a compelling reason to do that. I don't think they can. If it's not a content discrimination, the city can say we just decided this was a reasonable thing to do, and they normally can get away with it. The question is whether that kind of difference, not content in the sense of viewpoint that is, not favoring liberals over conservatives or the other way around. But it's content-based in the sense that what's your sign for? Is it for a political campaign? Then it can be a big sign. Is it for an event that's temporary? It has to be a little sign. That's content but in a different way. What the court ought to do is say that's not content based. There's no to have strict scrutiny of that kind of decision. It doesn't threaten to harm anybody because of minority status or political views or anything like that. They ought to have the latitude. This course has not very tuff on First Amendment cases. It wouldn't surprise me if it's content-based and the city needs to have a strong reason to do it.

Ted Simons: There was a split there.

Paul Bender: That's true.

Ted Simons: Did it surprise you?

Paul Bender: No, it's a very difficult, contentious issue around the country. How do you define content-based for First Amendment purposes? Content neutral things tend to be upheld.

Ted Simons: And not the only free expression case for the court, we have a couple of them, very quickly what's going on with these cases?

Paul Bender: They are both really interesting. The first one, Elonus, involved when you can convict somebody for threatening. He broke up with his wife and got really -- really was in bad shape and started to post things on his Facebook page which were threatening. A lot of them were just rap lyrics he quoted. But they seemed to say to his wife, I'm going come and get you. He was prosecuted under federal statue which makes it a crime to threaten people over the internet and things like that. He says he didn't really mean it as a threat, he was just letting off steam, he was venting as they say. The judge told the jury, if a reasonable person would think that that was a real threat, then he's guilty. He says the judge should have told the jury, you can only convict him if the jury believes he intended it to be seen as a threat. And the lower court said, they don't have to prove he intended it. And the court took that case? So the court again seems to be winding up maybe to be a very strong First Amendment case, and to free a whole lot of threatening stuff you would think ought to be able to be stopped.

Ted Simons: And including knowing the intent of someone who's --

Paul Bender: How do you do that? That surprised me. The other case involved judges who run for election. A number of states elect judges and that's a problem. Because when you run election you have to raise money. Who do they raise money from? From lawyers. Who do the lawyers go before to get their cases decided? The judges they just did or didn't contribute to. The states have said it's not a great solution but they have said judges cannot directly solicit money. They can't go to somebody and say please give me money. They can appoint a committee to do that but the judge shouldn't do it himself. This judge signed a fund-raising letter. She signed a fund-raising letter. And the question is whether you can be censured for that kind of free speech. The lower court said yes, and the Supreme Court takes that case. It sounds like they may be saying it's unconstitutionally for a state that elects judges to put limits on how the judges can campaign and raise money. The Court has held several times raising money for campaigns is free speech.

Ted Simons: As well as, we mentioned the Gilbert sign case, religiously focused if not targeted. But a couple of other religion idea here's. The Abercrombie and Fitch case deal with religion in terms of Muslims and how they practice.

Paul Bender: The Gilbert case is true, it's a religious group that wants to put up the sign. But I don't think the religious nature has anything to do with it. There is one who wants to grow a beard in prison. He wants to do it for religious reasons. Nobody doubts that there are sincere religious reasons. The state doesn't want to let him do it. He said, I'll keep it a half-inch, beard which seems to weaken his case some. If it's his religion, what's he compromising about? I think Scalia said something in the oral argument about that. The state says it's going to be dangerous. This case applies essentially the same statute involved in the hobby lobby case last year. It's the same standard. If you interfere with somebody's free exercise of religion you have to have a compelling interest, and you -- what you do has to be as narrow as possible to serve that interest. The issue in this case is does the state have a compelling interest to stop him from growing a half inch beard? Why is that danger? You can't hide much in a half inch beard. The state has come up with a number of reasons, and the court did not seem to be very friendly towards the state's argument. Maybe they are sort of embarrassed into it, having held that a business owner can impose his religious views on his employees in the Hobby Lobby case. Here is a Muslim with religious views. Are they going to say sorry, you can't exercise your religion in prison when they don't have a really good reason?

Ted Simons: Which brings up that Abercrombie and Fitch story.

Paul Bender: That is a Muslim young woman who wants to work in Abercrombie & Fitch. They have a dress code which says we've got to dress in the kind of clothes we sell, eastern collegiate wear. She wears a headscarf. So she asked a friend of hers, do you think my headscarf is going to be a problem. The friend asked the supervisor, who said that's not a problem as long as it's not black.

Ted Simons: Everyone looks better in black.

Paul Bender: She interviews for the job, the person who interviews her graded her very high and says she should be hired. He's worried about the headscarf. The woman was interviewed in the headscarf. It wasn't talked about at the interview. She goes to the district manager and says, what do I do about the headscarf? He said, don't hire anybody who wears a headscarf. The lower court said that's okay because the woman who wanted employment never said, I need to wear a headscarf for religious reasons, directly to them. In order to sue them for religious discrimination she has to affirmatively say, I need to do this for religious reasons. And say to them, will you let me have an accommodation. Since she didn't go through those steps she can't sue. The court took that case, again suggesting they are going hold what seems common sense. Everybody knows she was presented from wearing a headscarf because that's what Muslims do. That would be religious discrimination and they should make an accommodation for that.

Ted Simons: Interesting. Before we get you out of here, there's been talk of either Justice Ginsberg retiring or among some, mostly Democrats and liberals, that she should retire before President Obama leaves office.

Paul Bender: There is a very well-known liberal constitutional scholar has written an article saying she should retire. Because if she wants her leg ga he is to continue she should do it now so she'll be replaced by somebody nominated by Obama, somebody who would vote like her. If she waits Republicans may win the next presidential election and she would be replaced by somebody with different views. A number of people have said that. I think that is completely wrong and I think she is bright enough not to listen to that. When you have judges retiring based on their views staying alive, they are there for the wrong reason. They are not supposed to be plotting to have their legacy reinforced in the future.

Ted Simons: Has that been done historically? Have there been folks who have calculated their retirements?

Paul Bender: You never know for sure, I'm sure there have been but I think it's wrong. Because you should decide the cases before you. You shouldn't be planning what the Court's future is going to be. I want my cases to stand up and not yours. She is right not to do that. She is right now able to do the work. She enjoys doing the work. She does it very well from her point of view and a lot of people think she does it very well and she enjoys it. Why should she retire?

Ted Simons: We've got like one minute left now. That's not much time for this question. Is this still a Kennedy court?

Paul Bender: Yes.

Ted Simons: It is?

Paul Bender: Of course. It's been the same since Justice O'Connor left and was replaced by Alito. Four strong conservatives, and four moderates or liberals on the other side, Ginsberg and Breyer and Kagan. And Kennedy is the only one with any frequency who goes back and forth between those groups. He usually goes with the conservatives but not always. As we know primarily in the gay rights cases, but most cases that are close you said yourself, it all depends on what Kennedy is going to do. That's not going to change.

Ted Simons: Does that strike you as an overtly political court?

Paul Bender: I don't think he is politically partisan in a Republican Democratic way. I think he's quite conservative but I don't think he does it as a Republican. I don't know, I don't think so. There are I think people on the court who see things through a partisan lens. And I think that's one of the explanations for why those four people always stick together.

Ted Simons: Yeah.

Paul Bender: Because what they stick together on are the agendas of the two major political parties. That is very unfortunate from my point of view.

Ted Simons: Sounds like no one's swaying all that much from the four and the four.

Paul Bender: No. It would be a good development to get some people on the court who are not allied with either of those groups.

Ted Simons: Always a pleasure, good to have you.

Paul Bender: Same here.

Friday it's the "Journalists' Roundtable." We'll look back on the Arizona Secretary of State debate here on the horizon set. And a beheading video comes into play for the race for Congressional district 9. Those stories and more Friday on the "Journalists' Roundtable." That is it for now. I'm Ted Simons. Thank you so much for joining us. You have a great evening.

Paul Bender:Law Professor, Arizona State University;