Brain tumor experts at Barrow Neurological Institute at Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center have launched a revolutionary fast-track approach to cancer research. In partnership with The Ben & Catherine Ivy Foundation, the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) and the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, the “Phase 0 Trials,” shorten the evaluation of drug therapies for brain tumors from an average of five years to only six months. Dr. Nader Sanai, director of the Barrow Brain Tumor Research Center, and Dr. Michael Berens, TGen’s Deputy Director for Research Resources, will discuss the new research method.

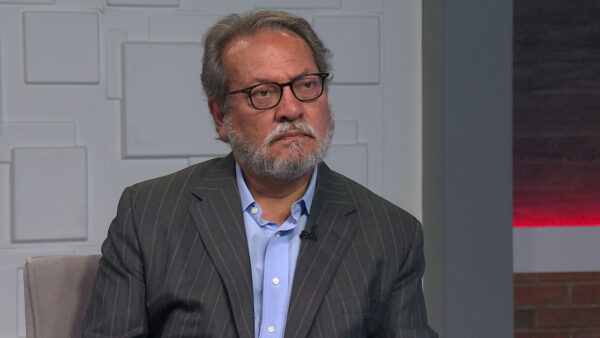

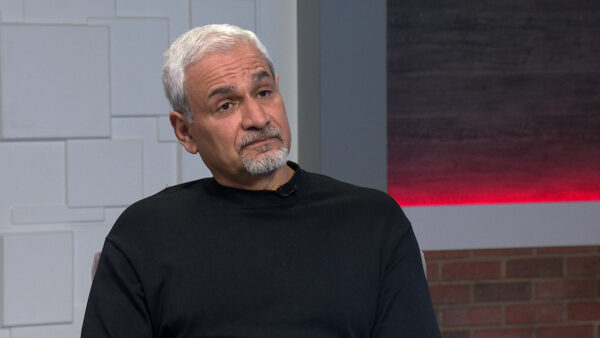

Ted Simons: Brain tumor experts at Barrow neurological institute in Phoenix have teamed with the Ben and Catherine ivy foundation, the translational genomics research institute, or TGEN, and the Barbara Ann Karmanos cancer institute to launch a new fast track approach to shorten the evaluation of drug therapies for brain tumors. Here to explain is Dr. Nader Sanai, director of the Barrow brain tumor research center, and Dr. Michael Berens, T-GEN's deputy director for research resources. Thank you for joining us.

Nader Sanai: Thank you.

Ted Simons: It is called a phase zero trial. What is this?

Nader Sanai: Phase zero trials are a way of testing a drug very quickly and finding out two things. Is the drug getting to the tumor and doing what it is supposed to be doing based on laboratory studies?

Ted Simons: You treat the patient, you remove the tumor, and then you watch the tumor, correct?

Nader Sanai: Basically. So, the patients get a dose of the drug before their operation. So, what we're able to do is remove their tumors, then test that tumor and say did the drug make it there and is the tumor responding to this drug?

Ted Simons: This sounds like something that should have been thought of -- am I missing something here? This sounds pretty logical.

Michael Berens: Well, it is very logical. I think most drug development in the past, you couldn't tell if the drug got to the tumor if the tumor responded. But brain tumors create a very different kind of scenario, where the growth of the tumor in the brain is behind what is called the blood-brain barrier. Other drugs used for other cancers tried against brain tumors, success rates of the trials are very small. We started to ask why would that be so poor? We realize we need better information about does the drug even get to the tumor?

Ted Simons: When you remove it after, even treating it before removal, you can then watch what happens because the drug is still doing its business, correct?

Nader Sanai: That's right. You have had an opportunity to expose to the tumor to the drug and you can ask that question quickly. And the reason that is valuable for our patients, that way they don't have to enter a study and find out five weeks or five months later it didn't work, we can find out immediately whether it will work or not.

Ted Simons: How is this different from traditional ways of study of brain tumor?

Nader Sanai: Basically the FDA commissioned the study a few years ago. Asked why are all of our drugs failing for brain tumor patients? They found for the majority of new drugs, what they do in humans is not exactly what they thought they would do based on laboratory studies. Mishmash between what we are learning in the lab and what is happening in us humans and they introduced this mechanism.

Ted Simons: Is that unusual or unique to brain tumors or do you see that often? Something that should be doing X is really doing Y?

Michael Berens: Well, it is definitely a case for brain tumors. Another tumor that commonly walls itself off with connective tissue or pancreatic cancer, they tend to be very difficult tumors to get drugs to. So a phase zero trial would be interesting in that case. Developing ways to create a way for more drug to get to the tumor. In the case of the brain tumor, it is clear what the anatomical or structural problem is, blood/brain barrier. And it is a great solution to say gosh we have all of these other great drugs out there for other cancers. Which ones can we use for brain tumors? This is a fast way to figure this out.

Ted Simons: Brain tumors and pancreatic cancer seems to be very similar Now you can remove the tumors and again watch what happens -- sounds like Dr. FRANKENSTEIN or something, you remove and then watch.

Michael Berens: It's not a real time progression of watching the tumor after it's removed. We do analysis - can we find a drug in a tumor. That destroys part of the tumor when you look for the drug. We also look for signals that the drug hit the target. Did the square peg get into the square hole for the tumor and do you see the change in the biochemistry, wow, the drug got there, hit the target, and consequences are actually happening. And that is exciting to piece that together on a patient by patient basis.

Ted Simons: It sure is. Why is this happening now?

Nader Sanai: The field has been slow to recognize the fact that a lot of our efforts haven't panned out the way we would like. 30 years ago, many people thought we would have cured brain tumors by now and we still haven't done it. Massive rethink in the field and there are market forces, pharmaceuticals that make studies like this more viable.

Ted Simons: I was going to say, market forces would suggest a quicker turn around more amenable to get folks involved.

Nader Sanai: Absolutely, many pharmaceutical companies burnt in this field, the market size is not as large as other cancers, consequence is less of a desire to enter it, long term prospects plus high costs.

Ted Simons: Is this the kind of thing happening around the world and new to the U.S.? Or is it new period?

Michael Berens: I think it spearheaded in the U.S. There are bright groups committed and involved and courageous patients saying we're willing to be part of this. How can we help advance the field and how can you learn about my cancer on a patient by patient basis? Courageous patients say let's work together and make a difference. And the Ben and Catherine Ivy foundation, how can we make something happen that otherwise might move slow or not happen at all? That support comes together and good things happen.

Ted Simons: Valuations from maybe five years to six months --

Nader Sanai: That's right. Typical trial takes six months to complete for a typical patient. They get the answer in two weeks. Before they have even fully recovered from surgery, they know whether or not this drug is going to be good for them or not. If it is not, they can move on to the next candidate and if it is, this is an option.

Ted Simons: How do you move on to the next candidate? You have already treated with drug X, I mean, if it is not working, how do you get drug Y in there?

Nader Sanai: The reason we give them such a short course of the drug so that it won't interfere with subsequent therapies. They are open to have any other experimental therapy available to them once the trial is over, which is over shortly after surgery.

Ted Simons: These trials started when?

Nader Sanai: Late last year.

Ted Simons: And what kind of results, responses are you getting from all of this?

Nader Sanai: The response in various ways. One, does this drug we're studying, inhibitor of one of the mechanisms for cell growth, does it get to the tumor? We would say the early look says we think there is reason to continue the study and we are seeing that the drug get to the tumor. So that's exciting. We are seeing some signals of efficacy. We will finish the full study. I think 24 patients will be evaluated and we will collect various parameters around the study. It's positive and we hope it leads to ways for us to know which patients should get this drug.

Ted Simons: Interesting, yes.

Michael Berens: And then we start to customize treatment to the patients.

Ted Simons: And it is more than sniper as opposed to the elephant gun kind of thing here. And you mentioned pancreatic -- can they be used by way of treating other cancers?

Nader Sanai: Sure, it can. Similarities in brain tumors, pancreatic cancers, several levels. Two of the least survivable tumors -- this works for other tumor types as well.

Ted Simons: Very encouraging news. Thank you for joining us.

Ted Simons: Thursday on "Arizona Horizon," hear from both sides on a bill that would ask voters to reconsider the clean elections campaign finance system. We will learn about an art auction designed to help the Phoenix art museum. That's at 5:30 and 10:00 on the next "Arizona Horizon." That is it for now. I'm Ted Simons. Thank you so much for joining us. You have a great evening.

Video: "Arizona Horizon" is made possible by contributions from the friends of eight, members of your Arizona PBS station. Thank you.

Dr. Nader Sanai:Director, Barrow Brain Tumor Research Center; Dr. Michael Berens:Deputy Director for Research Resources, Translational Genomics Research Institute;