Arizona’s Allure: A brief history of Arizona tourism

July 7, 2021

“Grand Canyon with Rainbow” Thomas Moran 1912

By Franco LaTona

Each year, visitors from across the globe visit Arizona for sight seeing at the Grand Canyon, camping in Roper State Park, hiking at Sedona’s Bear Mountain Trail and golfing in January.

Tourism is big business, and 2019 was the industry’s best year ever, said Josh Coddington of Arizona’s Department of Tourism. The state hosted 46.8 million overnight stays, and raked in $25.6 billion in direct travel spending.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic. But as more people get vaccinated and are able to travel safely, and with many Arizona state parks recently reporting more visitors, Coddington said he’s hopeful for a strong comeback.

“Thankfully, we have one of the wonders of the world,” Coddington said.

Not only does the Grand Canyon see millions of visitors annually, it was one of the original drivers of Arizona’s tourism industry.

At the end of the 19th century, America’s professional class was reading magazines like Scribner’s Monthly, where in 1875 John Wesley Powell published his “Explorations of the Colorado and its Canyons.” And as the U.S. economy shifted, a growing number of Americans had enough money to leave work temporarily and explore the wondrous west depicted in magazines, according to Daniel Milowski, a Ph.D. candidate in history at Arizona State University whose research focuses in part on community development and settlement in America’s southwest.

One of the first to capitalize on the influx of visitors was John Hance. In 1883, he settled near the Grand Canyon in search of gold, silver and asbestos. When that endeavor failed, the grizzly pioneer used his mining trails for tours, leading adventure-seeking customers on explorations down the canyon. A natural storyteller, Hance entertained his guests with tall tales, claiming he had dug the canyon himself, or that his horse Darby could ride across the canyon “by galloping atop banks of fog.”

“He just made stuff up,” said Arizona historian Jim Turner, author of the book “Arizona: A Celebration of the Grand Canyon State.” “And people loved him.”

Indeed, when President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Grand Canyon in 1903, it was Hance who led the tour.

But the advent of railroads around the turn of the twentieth century pushed out entrepreneurs like Hance in favor of commercial developers eager to capitalize on the Grand Canyon’s growing allure.

The Santa Fe Pacific railway (a subsidiary of the Atchison & Topeka Railway Company) laid the first tracks on the canyon’s south rim in 1901. The company stirred interest through marketing materials, notably sending copies of renowned artist Thomas Moran’s Grand Canyon painting to schools, libraries and railroad customers around the country.

“That classic iconography of the American Southwest that we associate with railroad tourism…is really the creation of the marketing department of the Santa Fe Pacific,” Milowski said.

The railroad also partnered with Fred Harvey, an innovative entrepreneur who became known as the “Civilizer of the West” for building hotels and restaurants along the Santa Fe Pacific railways from Kansas to California.

His diners, known as Harvey Houses, were the first U.S. chain restaurant, replacing often rotten railroad food with warm plates of steak, eggs, hash browns, pancakes, apple pie and coffee for 35 cents.

Harvey replaced his all male wait staff in 1883 with young midwestern women between the ages of 18 and 30, and dressed them in pristine white uniforms. The “Harvey girls,” as they became known, were immortalized in the 1946 film by the same name starring Judy Garland.

And Harvey Company hotels proliferated in Grand Canyon village–places like the Hopi House, Phantom Ranch and El Tovar, all still intact today. La Posada, a hotel in Winslow, was built in 1930 along the Santa Fe Pacific rail line on the way to the Grand Canyon. The Escalante, a luxury hotel in Ash Fork, was a Harvey Company creation built in 1907 on the junction line with Phoenix. Popular amongst wealthy travelers, the hotel included a telephone, hot and cold running water, bathrooms and showers.

“Fred Harvey was really a master of…knowing his clientele,” Milowski said.

Indeed, most big-city tourists wanted an adventurous exploration of the west, so long as the linen sheets and fresh cocktails they’d grown accustomed to back home were at arms reach.

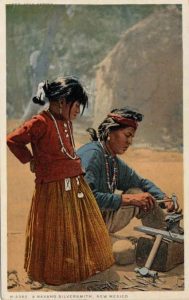

Recognizing this renewed interest, the Harvey Company set up curio shops at railroad depots and inside hotels, providing tourists with Indian-crafted artifacts and souvenirs. Starting in 1926, tourists could book “Indian Detours” along with their hotel reservations, taking curious passengers on visits by car to Native American communities like the Hopi reservation in northeast Arizona.

Left: This photo of a Navajo silversmith was used for a postcard produced by Fred Harvey’s company around 1909-1919. Original held by the Newberry Library. Right: Iconic Monument Valley draws visitors from around the world to Navajo Nation. Courtesy of the Arizona Office of Tourism.

“There would be demonstrations of Hopi craftwork, Hopi cooking,” Milowski said. “But you were being shown an idealized version…on these tours. You would have been spared the more negative aspects of essentially the American takeover of the southwest.”

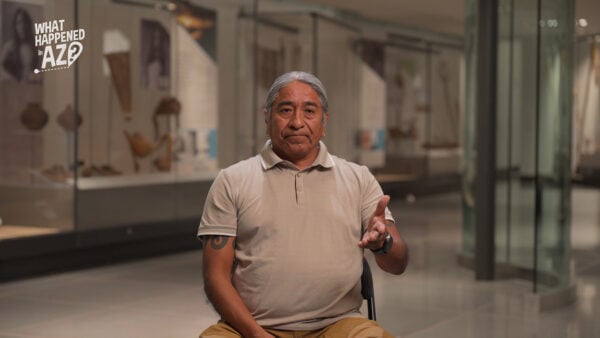

Arval McCabe of the Navajo Nation’s Tourism Department agreed, and noted Native Americans were poorly compensated for their participation in Indian detours. Native American art and craftwork was also undervalued in curio shops, McCabe said.

“People were often cheated…during the haggling process,” he said in an email.

Today, as people visit the Navajo Nation for its breathtaking sites like Monument Valley, Canyon De Chelly and Shiprock to name a few, McCabe said his office works to ensure culturally accurate information is disseminated to visitors.

While the Grand Canyon almost exclusively drove tourism during the railroad years, that began to shift after the advent of automobiles, Milowski said.

Cars preceded decent roads, however, and up until the 1930’s, Milowski said Arizona invested almost nothing in road construction. But this was a draw in its own right, Milowski said. “The idea was that you could…test your mettle as a man by piloting through roadless Arizona,” he said.

Tombstone started drawing more visitors, too. Arizona historian Jim Turner said best selling books like Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshall and Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest created a new fascination with a “wild west,” where lawmen and outlaws warred in dusty streets outside saloons. In 1929, the first Helldorado celebration launched in Tombstone, complete with a reenacted gunfight.

The Wigwam Motel in Holbrook, Arizona, built in 1950, reflects the popularity of Hollywood Westerns at the time. One of several such motels built across the United States, neither the name nor the design bear any particular connection to Native cultures in Arizona. Photo by Jim Turner.

“You’ve got a different class of people,” Turner said. “They wanted the shoot’em up stuff.”

While the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 produced the first version of Route 66, it largely remained gravel until Franklin Delanor Roosevelt and Congress poured money into America’s infrastructure through the New Deal.

“Once you have essentially coast to coast paved highways, then tourism by automobile really takes off,” Milowski said.

More cars meant greater demand for lodging. Dude ranches began popping up around the state, Turner said, as did mom and pop “motels,” though sometimes they amounted to little more than glorified campgrounds, often attached to gas stations. Roadside attractions became popular as well.

Courtney Lamb, a graduate history student at Claremont University who presented on tourism at a recent Arizona Historical Society convention, said animal displays became a popular tourist draw in the early twentieth century. Entrepreneurs with local and exotic animal collections often partnered with essential stopping places like filling stations.

“[Tourists] will stop for gas, and ‘oh, here’s this guy with these cool animals. Let’s give him a couple of bucks to see the show,’” Lamb said.

Lamb said most early roadside attractions were owned by people with personalities as big as their collections. The eccentric Harry E. Miller entertained travelers in Two Guns, Ariz. (now a ghost town), by claiming Apache heritage, even referring to himself as “Chief Crazy Thunder” while showing them his collection of mountain lions, lynx, snakes and gila monsters.

“He was really playing a character,” Lamb said.

George Curtis, the founder of Apache Junction, started his roadside animal display in the 1920s. In the 1930s, he received a permit from the Arizona Game and Fish department, making his collection the first official zoo in the state. Beginning with only his chimpanzee Jimmie, Curtis added other native and exotic animals, including a black bear, Sonoran white-tail deer and rattlesnakes.

Ostrich farms also became popular in the 1900’s as their feathers became fashionable, Lamb said. In fact, Chandler’s founder, Dr. Alexander J. Chandler, was fascinated with the exotic creatures, cultivating his own ostrich farm at his ranch in Mesa. Since 1988, the city has held an Ostrich race every year in his memory.

After World War II, tourism by automobile exploded, according to Milowski. And with better roads, smaller attractions became destinations in their own right. Oak Creek Canyon, for instance, near Flagstaff, became a popular tourist spot, Milowski said.

Recognizing a drastic increase in traveler volume, themed restaurants, themed hotels, go kart and amusement parks proliferated along highways, often positioned on the way to larger destinations like the Grand Canyon, Milowski said.

“[You get] those igloo themed, TV themed…spaceship themed places all over the map,” he said. “The place you’re staying is an attraction in its own right.”

But access to spaceship themed hotels and burger joints wasn’t equal. While white travelers generally roamed freely in Arizona, African Americans experienced something entirely different. Originally published in 1936 with over two million subscribers at its peak, The Negro Motorist Green Book listed African American friendly businesses throughout the country.

In Arizona, all of the Harvey Company businesses were included, but that was more the exception than the norm, Milowski said. And as many Harvey Company businesses closed mid century, travelers of color had limited options. Indeed, outside major cities like Phoenix and Flagstaff, the state of Arizona, particularly the northwest portion in cities like Kingman, were rather unfriendly towards travelers of color, Milowski said.

The completion of the interstate highway system in 1955 marked the decline of themed hotels and roadside attractions, Milowski said. Travel between major U.S. cities became easier, meaning stops were shorter and less frequent. That same year, Disneyland was built in Anaheim, CA, and large attractions like SeaWorld and Six Flags followed, overshadowing their smaller counterparts.

Today, visitors are drawn to Arizona for myriad reasons, from fishing and bird watching to stunning national parks and monuments to golf and spas in February, and more.

And while the pandemic has curtailed tourism in Arizona, Milowski said this isn’t the first time people feared the industry’s demise. He said much was written during the great depression and the Great War about the tourism’s possible end, only for it to bounce back stronger than before. Milowski said he believes in this respect, history is likely to repeat itself.

“I suspect it will come roaring back,” he said. “Arizona has these things that no one else has, like the Grand Canyon, and the fact that it’s 70° in January.”

There’s far more to Arizona tourism than we could fit in this story! Tell us your favorite Arizona destination on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram – we’re @ArizonaPBS!

Explore Arizona in these Arizona PBS productions:

Find them online or on the PBS Video app.

Beyond the Rim: The Next 100 Years of Grand Canyon National Park free to all viewers

Under Arizona available to PBS Passport users

Can’t-Miss Arizona Destinations

The Hassayampa River Preserve near Wickenburg offers guests a beautiful riparian area that’s full of trails with plenty of spots for picnicking and birdwatching.

Roper Lake State Park near Safford is an ideal spot for camping. Guests can bring an RV, pitch tents or rent one of the cabins on site. In addition to hiking, visitors can enjoy fishing, swimming and boating on the lake.

Pine Creek Canyon Lavender Farm. Originally built in the early 20th century, this lavender farm offers guests a variety of handcrafted products including soaps, lotions, lavender creamed honey, lavender salt and much more.

Saguaro National Park is located on the east and west sides of Tucson. Home to the nation’s largest cacti, visitors can view the breathtaking scenes by driving, hiking, biking or horseback riding through the reserve.

Monument Valley is one of the most photographed natural landscapes in the U.S., and has been featured in numerous Hollywood films. These iconic red sandstone buttes on the border of Arizona and Utah are a destination as essential as the Grand Canyon.

This story was originally in the Summer 2021 issue of Arizona PBS magazine.