A string of canceled speakers on university campuses has reignited the debate what should be protected as free speech on a college campus.

First Amendment lawyer Floyd Abrams says circumstances now are different from in the past. Previously, the debate centered around school administrations limiting speech, but now the issue is with students. According to Abrams, student bodies protesting and rejecting speakers on campus is “a sort of on-the-ground suppression of speech.”

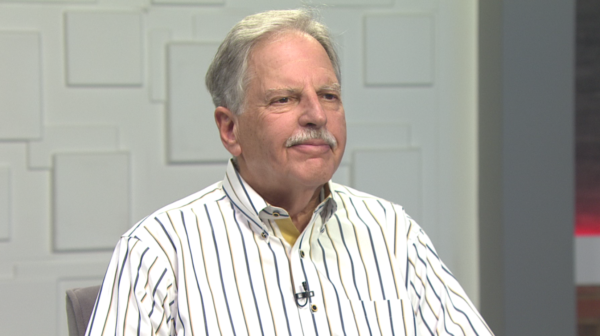

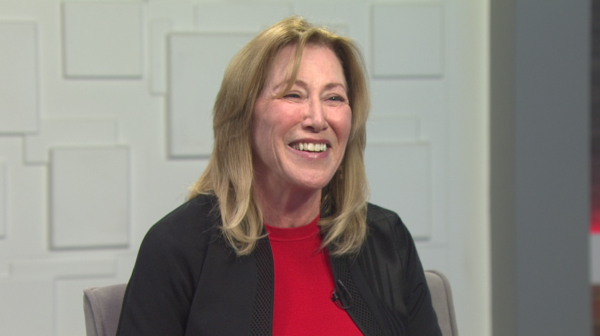

Ted Simons: Recent events involving members of the alt-right movement speaking on college campuses has sparked a debate about what constitutes protected speech. Noted 1st-amendment attorney Floyd Abrams recently joined us to discuss free speech and intellectual diversity in higher education. Thank you so much for joining us on Arizona "horizon." Good to be here.

Ted Simons: Good to see you. You are here as part of a series regarding free speech and intellectual diversity on college campuses and higher education. How much freedom of speech is there on university campuses?

Floyd Abrams: In theory there is a lot and I think in fact there is a lot. But what has been going on is a sort of on-the-ground suppression of speech at a lot of colleges and universities around the country where people are asked to come speak and then there is objection to them and then invitations are withdrawn or people comment and shouted down. Those things are new. That is not a norm and it is becoming more and more prevalent as the years past.

Ted Simons: Why do you think that is?

Floyd Abrams: I think the country is breaking up in a lot of ways. Most of the on campus issues these days, are not administrations cracking down on speech which was much more the case when I was in college and people were limited in what they could say. Students who were offended by people who were excited or students who believe or accept the notion that because some speakers are truly reprehensible in their views that they therefore shouldn't be allowed to have a forum or other students shouldn't be allowed to invite them. Things like that are what raise a lot of the most major persistent problems.

Ted Simons: What about policies, though, that target hate speech? University policies. What is out there? Is that censorship?

Floyd Abrams: Hate speech is basically protected under the first amendment at least on state university college campuses because as a legal matter we treat a state university as if it is the state. In America alone, in the world, unlike Canada, unlike Western Europe, democratic countries all, is very, very tolerant of allowing disreputable and disagreeable and even racist speech. What universities are facing now is what to do when speakers come who are white nationalists or voice and are indeed invited sometimes because they voice racist statements. So it is not easy. It is very hard for university administrations and disagreement to students who feel affronted or pained or really harmed by some of the speech we allow.

Ted Simons: When does that pain and hat harm equate to we can't allow this person to speak on campus?

Floyd Abrams: As a legal matter, as a first amendment matter, hardly ever. If we have a situation where someone is literally inciting people to riot that is one thing. But we are having more and more cases now involving racist speakers who are invited by a very small minorities of students at colleges who want to hear them, or want to make trouble, or see what happens, and the legal answer is it isn't hard. The schools have to allow them. It is a real risk if the problem is violence. Then as a general proposition, state schools at least have to deal with it by bringing the police, by doing things to try to prevent or subdue violence. Or if people have been involved in a past with violent activities and the same thing. Racist, nasty speech is protected in America.

Ted Simons: Do protesters have the right to shut down and interrupt speakers?

Floyd Abrams: Certainly not the first. They don't have a right to shout down. They have the right to protest, they have the right to have signs, they have a reasonable right to heckle a little bit but it has to stop well before we are suppressing the speech itself. The speech has to go on. We can't allow what we call, and this is the word we use in the law, a heckler's veto. We can't allow people who because they are so offended from the speech to prevent it by heckling or screaming. A lot of different ways have been tried. Sound trucks and other mechanisms to, in some cases, successfully prevent speech. That has led to some litigation.

Ted Simons: I was going to ask if that does occur, and the speaker is shouted down and has to leave and can't make their speech, can they sue?

Floyd Abrams: Yes, or at least the people, again, who invited them. Like San Francisco state, for example, is being sued now because the mayor of Jerusalem was invited to speak and was shouted down by anti-Israeli students and effectively barred from speaking and that has led to litigation brought by students who say I wanted to hear him. That sort of litigation I think is going to be more and more common.

Ted Simons: The idea that conservatives say they are the ones that are being targeted here most often on campus. You buying that?

Floyd Abrams: Yes.

Ted Simons: Why do you think that is?

Floyd Abrams: I think it is two things. One conservatives are generally a minority on campus out of sync with the more general, liberal on campus. But at the same time, it tends to be conservative speakers who are saying the more outrageous and sometimes threatening sounding thing when they do engage in speech. I am not talking about an American conservative senator here and there. We are talking again and again about people who enjoy and often say things for the purpose of inciting reactions. You know, it really has to be said and our whole system is based on the notion that we don't trust government or government entities to make decisions about who speaks and what they say.

Ted Simons: So for the students that say, so a Nazi, someone who supports Nazism, is speaking on the campus. If we don't shout that person down, those ideas get leveraged, they are sustained, they are allowed to flower, they are allowed to grow which nothing good, according to these students, nothing good could come from that ideology getting loose, free and purchased if you will.

Floyd Abrams: The only thing that is good is allowing speech whether we like it or not -- whether. The only thing that is good is keeping the government from deciding who speaks and doesn't speak. That is why we do it. We don't allow Nazi speech because we think it has any value to it. We allow it because we are so committed to the notion that free speech has to be the norm and free speech from what the government even at its very best, trying to only do the right thing, might like to do.

Ted Simons: Last point here. Supreme Court Justice Brandice said the answer to hate full speech is not enforced silence but more free speech. Sounds like you agree with that?

Floyd Abrams: I do agree with that. Really it ought to be said that is a very hard standard to live by. We really have to understand and accept the proposition if we agree with the justice, as I do and as the courts generally have, we will have some amount of nasty, offensive, outrageous speeches for the greater good of subexpression that speech.

Ted Simons: Thank you for being here.

Programming note: tomorrow on Arizona PBS we'll air a special half hour discussion with Floyd Abrams. The show, free speech: challenge of our times, airs tomorrow evening 7:30. And tomorrow on Arizona horizon, it's the journalists' roundtable, the governor moves to save health-care coverage for children from lower-income families. And the Maricopa county recorder apologizes for inflammatory on-line comments. That's on the next journalists' roundtable. I am Ted Simons. Thanks for joining us. You have a great evening. Arizona "horizon" is made possible by contributions from the friends of Arizona PBS, members of your PBS station. Thank you.

Floyd Abrams: First Amendment Lawyer