New study reveals mammal diversity continues to grow

Nov. 20, 2025

Hundreds of years of discovering thousands of mammal species would lead us to believe that, by now, science has found and named every kind of mammal that exists; however, according to a study, mammal diversity is not finite.

A new study published in the Journal of Mammalogy reveals that our understanding of mammal diversity is expanding, and at a rate faster than most people realize. The study was led by Arizona State University researchers in collaboration with the American Society of Mammalogists. It outlines which mammal species exist, where they live and what efforts are needed to better protect our biological heritage.

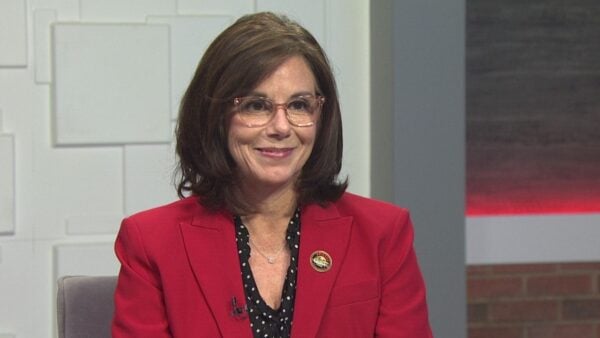

Associate Professor, School of Life Sciences at ASU, Nathan Upham, joined “Arizona Horizon” to expand on newest studies found on mammal diversity.

Right now, the database includes approximately 6,800 recognized mammal species, but that number is far from final.

“We’re adding about 65 species per year,” Upham said, noting that the total could reach 8,000 by 2050 if current trends continue.

The increase comes from two major drivers: improved genetic technology and expanded global collaboration. DNA sequencing now allows researchers to identify cryptic species, animals that look identical but are genetically distinct, and to clarify which populations truly represent separate species.

At the same time, more scientists in biodiversity-rich countries such as Brazil, Indonesia and regions of Africa are leading field studies that uncover previously undocumented mammals.

Upham noted that mammal diversity is heavily concentrated in two groups: rodents and bats, which together account for about two-thirds of all known mammal species.

Rodents’ ever-growing incisors allow them to adapt to varied environments, while bats remain the only mammals capable of sustained flight, a trait that has helped them diversify across nearly every continent.

Beyond counting species, the study emphasizes why classification matters. Scientific names form a universal language that helps researchers understand ecosystems, track predator–prey relationships and monitor how environmental changes affect wildlife. They are also essential for studying viruses, many of which originate in mammals.

Despite centuries of research, Upham said many mammals remain unknown to science, especially in remote or tropical habitats.

“We’re still refining our understanding of who’s out there,” he said.