U of A receives $14.8 million grant for Superfund program

Nov. 17, 2025

The University of Arizona Superfund Research Center has received a $14.8 million, five-year grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, a division of the National Institutes of Health. The grant will be used to fund research projects to understand and mitigate health threats from contaminated dust from mines and hazardous fungal spores inside mining communities.

The Superfund Research Center, also known as “The DUST Center: Hazardous Dust in Drylands- Exposure, Health Impacts, and Mitigation,” was established in 1989 and has been continuously funded by the NIH since 1997. Its work focuses on mining towns and Native Nations across the Arizona-Sonora border region, where residents face chronic inhalation of arsenic-rich dust from mine tailings – waste left over from mining operations. This new round of funding will support four new integrated research projects.

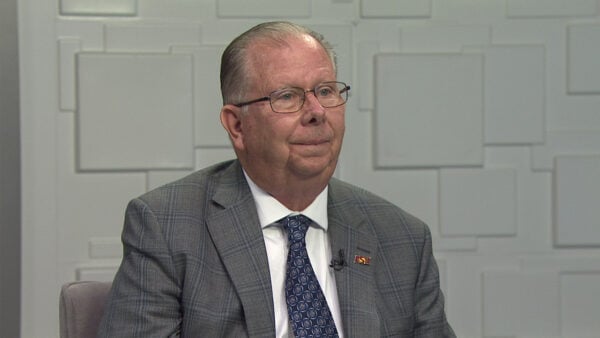

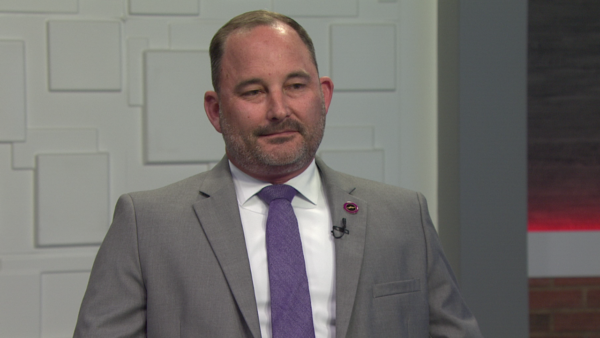

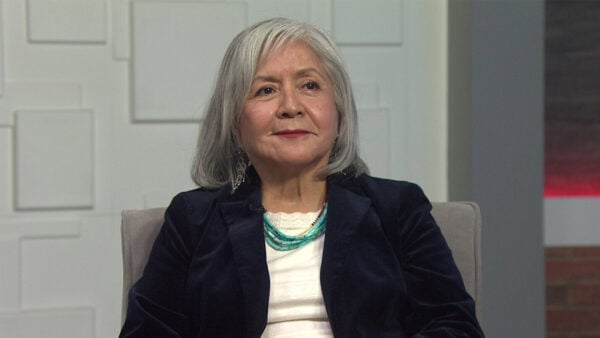

Professor Xinxin Ding, U of A Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, and Professor Raina Maier, U of A College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences, joined “Arizona Horizon” to talk more about what this grant means for the Superfund Research Center.

Ding explained the urgency behind the work, noting that Arizona’s mining communities face unique combinations of environmental hazards.

“We all know that here in Arizona we’ve got lots of dust, particularly in certain regions,” he said. “We’re trying to figure out what’s actually in the dust, the chemicals, the toxic metals, and what exposures we get, and how to prevent it.”

One of the Center’s major concerns is the presence of arsenic in airborne particles. Ding said the dust contains “arsenic… one of the major toxic metals,” and warned that fungal spores, such as those that cause Valley fever, often travel attached to these same contaminated particles.

“The particles have spores attached and metals attached, and the spores interact with the metals to perhaps make the metals more toxic,” he said.

Maier highlighted decades of field observations showing that mine waste does not remain confined to mining sites.

“We know that windstorms blow mine tailings into the communities and cause exposure,” she said, adding that researchers have already found “elevated concentrations of metals that people are exposed to” inside homes and yards near waste piles.

The new grant will fund four research projects, two biomedical and two environmental. Ding described one biomedical project as an effort to understand “how arsenic and other metals in the particles make the airways more vulnerable to infection by fungal spores.”

Another will study which specific components of dust are most harmful to lung tissue.

Maier oversees the environmental research, including efforts to reduce dust emissions through revegetation.

“If you vegetate, you can suppress dust emission, and that solves the problem,” she said. Her team is studying plants that can survive in mine tailings, either by stabilizing metals in the soil or accumulating them so they can be harvested.