The ability to alter genes for our own benefit also has the potential to be harmful to us. Arizona State University evolutionary ecologist Jim Collins is urging scientists to consider the scientific, ethical, regulatory and philosophical implications of genetic alterations. He will discuss the complicated question of the benefits and costs of genetic alteration.

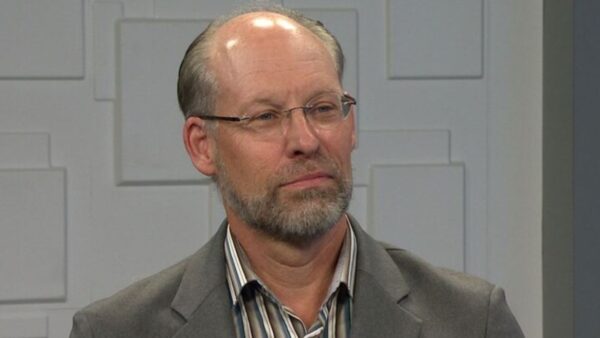

Ted Simons: Gene modifying technology is increasingly being seen as a way to eliminate everything from invasive species to eliminating certain insect-borne diseases. But ASU evolutionary ecologist James Collins wants scientists to consider the ethical, regulatory and philosophical implications of genetic alterations. James Collins joins us now to discuss gene modifying technology. Good to have you here.

James Collins: Thank you.

Ted Simons: This is -- this kind of stuff is fascinating. Because you really, as you're trying to point out, you really don't know what you're getting into completely, do you?

James Collins: It's really hard to make predictions in these sorts of biological systems. It's much the point of what we've been talking about. It falls into the category of what some of my colleagues call anticipatory governance. It's the notion of anticipating what some of these changes might be, and putting in place the sort of regulations that would be really helpful in helping us control these technologies as we start to potentially put them in the field.

Ted Simons: What is gene modifying technology? What are gene drives?

James Collins: So it would be a case in which you combine mathematics, engineering, biology, to alter the genome in very predictable ways and do it quite quickly, with changes that you can then have individuals perpetuate from time to time. And therefore push this change through a population much more efficiently than has been done in the past.

Ted Simons: Correct me if I'm wrong, I'm wading in deep here. RNA program to edit precise DNA sequences. Is that in the ballpark there?

James Collins: That's in the ballpark. The engineering part of this uses the RNA, the messenger molecule, to change the basic genetic machinery of an individual. To put a simple example on the table, it would be a case where you would use one of these gene drives, for example, in a species that has two sexes, males and females, where the sex of a baby is determined by the male whether it produces a male chromosome or a female chromosome. The males would produce only male chromosomes. Meaning that eventually you wind up with a population or species that's all males and the bisexual species goes extinct.

Ted Simons: If it goes extinct and it's responsible for insect borne diseases,that's a good thing.

James Collins: It's easy to see why there's an argument for driving to extinction some types of species. There are species in sex that carry vectors for malaria, dengue fever, reducing that sort of burden on human populations.

Ted Simons: What are the concerns?

James Collins: We don't know enough about the role of insects in the basic biology, basic ecology of these ecosystems to make a prediction about what the consequences are of losing a species even like a mosquito from the ecosystem.

Ted Simons: If you're looking to get rid of an invasive plant, you're going get rid of it but you don't know what else you'll get rid of.

James Collins: That's right, that's right. It's not unlike any kind of technology. The upside is the capacity for reach in and eliminate an invasive species. The downside could be you don't have sufficient control over the genome and it could get out into a beneficial species.

Ted Simons: I was going ask about the stability of this. It sounds good, sounds like it lasts, but we don't even know if it lasts, do we?

James Collins: Right, right. There's a lot of basic research that's needed there. The problem is really quite interesting. You have basic research advances and applied research coming in right on top of it. You can see the two things going together but we don't know enough on the basic side to make the kind of predictions you want in order to use it in very responsible ways on the applied side.

Ted Simons: So again, when we were talking about -- I think you just referred to it moving from species to species, that's possible as well that. Sounds really tough.

James Collins: It is possible, because we know that in the natural world there are such things as lateral gene transfer, when genes move between different species. In fact, it's been a key part of the evolutionary process over time.

Ted Simons How far along are we with gene modifying technology right now?

James Collins: We've had some gene modifying technologies for quite a while. Genetically modifying organisms we have. The issues with these new techniques are, are we able to do it very precisely, very quickly and get changes that are very different from the organisms we have right now.

Ted Simons: And with that in mind, what kind of safety measures do you think are needed out there?

James Collins: We need to be able to step back. These technologies are imagined and being brought forward. They have groups of individuals that we argue in our paper are by definition interdisciplinary. You really want philosophers, ethicists, scientists, engineers all sitting at the table and you want ordinary citizens at the table discussing what the pros and cons are of doing these sorts of technological advances.

Ted Simons: Let's say the mosquitos.

James Collins: Sure.

Ted Simons: People are sitting at a table what, are they saying?

James Collins: They are saying the advantages from their perspective and what the disadvantages might be from the perspective of an individual who doesn't quite agree. Somehow you have to bring these voices together in a way that you come to a decision that's responsible.

Ted Simons: That is happening to a certain degree now? You may not think it's happening enough but is it happening to a certain degree?

James Collins: It is, to a certain degree. We have experience in other sorts of areas. And bringing these sorts of committees and discussions together to make decisions about the best way to move forward.

Ted Simons: How is it being handled? Obviously you can get roundtable groups and these sorts of things but how are you getting these sorts of people together?

James Collins: In our case we use a pair of workshops we organized at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the other at University of California at Berkeley. We had scientists, agency people, we had people from EPA, all sitting at the table, philosophers. All sitting at the table and having these discussions about how they think the best way forward might be.

Ted Simons: Are they specific on certain invasive species or kind of looking at the big picture and basically more of a big umbrella kind of a thing?

James Collins: Kind of a combination of both. We have power workshops with individuals coming in with very specific cases. They were at the leading edge of this sympathetic biology technology. Then you draw on that to see what types of generalizations might be able to come forward.

Ted Simons: If you're actively working in the lab, and you've got a eureka moment here, are you going to pull back because some philosopher says, wait a minute, be careful.

James Collins: We are charged to think in that way at all times. Yes, that's exactly the issue being put on the table. There's a together which you want to be responsible. Us a begin to think through what these advances could be. And furthermore, how you can use them both to advance basic science but also to advance in the applied area.

Ted Simons: How does the business world get into all of this? A lot of scientists are developing a lot of things for profit, for industry. How does that play into all of this?

James Collins: Among the cases we had several of them were from business out of biotechnology. With one was a fascinating case in which the genes for bioluminescense, the genes that cause organisms in the ocean to glow at night, have been introduced into a small plant. Now the plant glows.

Ted Simons: Oh, my goodness.

James Collins: Glowing plants. And the question then is, what do you do with that sort of technology? It's being made available. You can get seeds for glowing plants. How do you monitor and regulate that sort of technology?

Ted Simons: Everything from insects getting the time of day wrong to birds getting the time of day wrong.

James Collins: That's the point. Especially from an ecological and environmental point of view.

Ted Simons: Last question: Is the march toward modification, is this inexorable? We can talk about this all we want. As human beings, this is going to happen, isn't it?

James Collins: I think these technological advances are there on the table. They are being brought forward. And the issue that again that goes along with this notion of anticipatory governance, a big word for a simple idea, getting in front of the technologies and having these conversations and making these decisions before they are released.

Ted Simons: I know you're having these conversations, but are people listening?

James Collins: Well, we're waiting to see if they are going to listen on this one. We do think they are listening, yes.

Ted Simons: Very interesting stuff. Thanks for joining us, very interesting.

James Collins: Welcome, it's been a pleasure.

Jim Collins:Evolutionary Ecologist, Arizona State University;